Written by Emma Stone

LSD can shake up a person’s worldview, turning it upside down and inside out. A powerful mood-changing and oftentimes unpredictable psychedelic compound, an acid trip often delivers a life-changing experience.

For many, LSD goes hand-in-hand with the psychedelic counterculture of the 1960s, with images of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. But this old school perception of LSD is undergoing an overhaul. Nowadays, psychedelic substances like LSD are experiencing a renaissance and are being investigated as mind-altering medicine.

What is LSD?

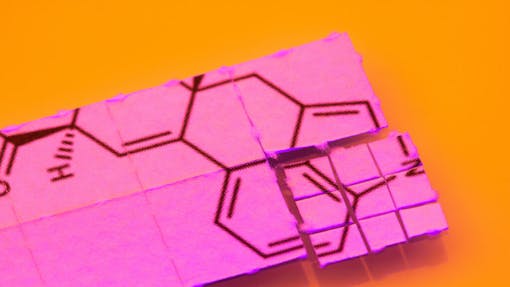

Lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD, is a semi-synthetic compound. The drug finds its origins in lysergic acid, which is formed in a parasitic rye fungus. When lysergic acid is teamed with diethylamine, a derivative of ammonia, LSD is produced, creating a substance that can unleash hallucinogenic effects on the consumer.

LSD is more regularly referred to as “acid,” along with a host of other colorful names that speak to its hallucinogenic effects: “Stamps,” “Lucy,” “Microdots,” “Purple Heart,” “Sunshine,” and “Heavenly Blue.” The drug is often dosed in hits, tabs, or “window panes,” and effects can set in as soon as 30 minutes after taking a dose, usually lasting from six to ten hours.

LSD, like all psychedelics, can also alternatively be classified as an entheogen. Entheogen literally means “to produce the God within,” and refers to the drug’s ability to induce mystical experiences. These mystical experiences are defined by a sense of oneness or unity with the surrounding world.

According to Carl Ruck, a psychedelic historian, entheogens enable the consumer to feel, “As if the eyes had been cleansed, and the person could see the world anew in all respects.”

What is the history of LSD?

In 1938, Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist, was studying derivatives of lysergic acid, systematically reacting the acid with other chemicals in an attempt to find a respiratory medicine. One of the compounds he synthesized was lysergic acid diethylamide, which he named “LSD-25.”

Tests on animals didn’t reveal any applicable medical benefits, but Hofmann did note that the animals became restless while under the influence of the drug. The drug was shelved but five years later, Hofmann found himself thinking about LSD-25 again. On April 19, 1943, Hofmann resynthesized LSD-25, and this time, he self-administered a dose. After taking 250mg, he rode his bike home and was flooded with the effects of the drug. This would later become “Bicycle Day,” a day to celebrate psychedelics.

In his book, he wrote:

“Here the notes in my laboratory journal cease. I was able to write the last words only with great effort. I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant, who was informed of the self-experiment, to escort me home… On the way home, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot… The lady next door, whom I scarcely recognized, brought me milk – in the course of the evening I drank more than two liters. She was no longer Mrs. R., but rather a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.”

Hofmann’s experiences launched a surge of work on LSD and other hallucinogens. LSD was used as an experimental tool to induce temporary psychosis by the CIA under their MK Ultra program. LSD was even studied as a drug that could improve eyesight.

In the 1950s, therapists began experimenting with LSD to treat conditions such as neurosis, anxiety disorders, alcoholism, and even opioid addiction. As research into therapeutic applications flourished, so too did LSD’s popularity among recreational consumers and spiritual seekers in the 1960s.

The passage of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act saw LSD classed as a Schedule I controlled substance. Despite short spurts of LSD-focused research in Europe, studies on LSD ground to a halt after 1970. That’s currently changing, however, with research into the compound picking up pace once more.

How does LSD make you feel?

In Hippie, Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho wrote: “You take LSD and think: Good God, how didn’t I notice that before, the Earth breathes, and its colors are constantly changing?”

Like many psychedelics, LSD can bring about a cascade of mental, emotional, and physical sensations. Individuals tripping on LSD often report visual distortions, colors appearing incredibly saturated, and numbers or words seeming to slide off pages. Many consumers share the experience of seeing the world around them breathing.

These visual extremes are often accompanied by intense changes in mood that can run the gamut from bliss to anxiety and fear. At one end of the spectrum, consumers revel in feelings of euphoria and a sense of peaceful certainty. On the other end, however, feelings of anxiety, dread, fear, or loss of control can take hold, causing a bad trip.

Set and setting play a critical role in governing how a trip will play out: “Set” is defined as “thoughts, mood, and expectations of the subject prior to treatment,” and “setting” as “the physical and interpersonal environment in which the subject undergoes treatment.” Bad trips are more likely to take place in uncontrolled settings or when a consumer isn’t in a positive state of mind. An LSD experience in a controlled situation, however, can lead to long-lasting, positive transformative effects on the individual.

An assortment of physical changes often goes hand-in-hand with these mental sensations, including appetite loss, insomnia, dry mouth, muscle tension, and the shakes. Being touched, and the experience of other bodily feelings, can be perceived as strange or bizarre.

LSD also fires up the sympathetic nervous system, which is involved in regulation of the heart, muscles, and glands in a response to stressful situations. As a result, an LSD trip can increase sweating, elevate heart rate and blood pressure, and even lift blood glucose levels.

How does LSD work on the brain?

While there’s still much to learn about brain activity on LSD, it appears the drug’s interaction with serotonin receptors is critical. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that enables communication between brain cells. It’s also a hormone that impacts diverse functions, including emotional regulation, mood stabilization, motor skills, movement, sleep, eating, and digestion.

LSD mimics serotonin in the brain. The body treats LSD molecules like serotonin, binding LSD with the brain’s serotonin receptors. These receptors have an even stronger affinity for LSD than they do for serotonin and “close like a lid” over LSD molecules so they cannot quickly detach. This allows the effects of LSD to linger for a long time.

Another fundamental way in which LSD is known to work on the brain is by inhibiting the default mode network (DMN). The DMN is not a physical part of the brain but rather a system of connected regions that play a role in introspective activities. Daydreaming, thinking about oneself or others, or ruminating on the past or future are when the DMN is most active.

By suppressing the DMN, psychedelics increase communication and integration across the whole brain. In scans of brains under the influence of psychedelics (you can see images here), the whole brain appears to light up as vision, attention, movement, and hearing networks become more connected and interactive.

The increased communication between high-level (thinking and associating) and lower-level (sensory) regions of the brain helps to expand awareness and overall function. By weakening the DMN and integrating the whole brain, a person experiences more fluid forms of thinking that overcome entrenched, rigid thought patterns.

How does LSD compare to other psychedelic drugs?

LSD is recognized as a “classic psychedelic,” along with DMT, mescaline, and psilocybin. While consumers of these compounds often report similar experiences, LSD is distinctive in some critical ways.

It takes just a tiny amount of LSD to kick start an intense, ten-hour trip. A shroom trip, in comparison, usually comes to a close after six hours.

LSD consumers often share more intense experiences while under its influence—both extremely good experiences and extremely bad ones. For this reason, experts stress that getting set and setting right is particularly crucial when taking LSD. The right mindset, situation, and context can produce a positive experience, while the contrary can result in a bad trip.

However, the actual experience of LSD has been found to be similar to shrooms. In one survey comparing the experiences of people taking LSD, psilocybin, and DMT, no significant differences were found between consumers who had taken LSD or mushrooms.

Ayahuasca was found to offer a more “spiritually significant” experience than LSD. Ayahuasca consumers reported enhanced life satisfaction, spiritual awareness in everyday life, and attitudes about life, self, mood, and behavior. The researchers pointed out that this could be because ayahuasca is frequently consumed in a religious or spiritual context.

The survey reported that DMT was more likely to initiate a mystical experience than LSD. Those who had taken DMT often described a visual or sensory interaction with a benevolent otherworld entity, or an experience of temporarily stepping out of time and space.

What is LSD used for today?

The LSD research renaissance is well underway. Experts suggest that LSD represents a potential tool in treating alcohol dependence, schizophrenia, and drug addiction. And as an extra bonus, it may also boost creativity.

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) recently completed a pilot study investigating LSD therapy to treat anxiety associated with end-of-life disorders. A follow-up study found that 77.8% of participants reported that LSD helped reduce their anxiety and 66.7% reported a rise in quality of life.

There’s a host of other LSD research initiatives taking place around the world too, including LSD therapy as a treatment for major depressive disorder, cluster headaches, anxiety disorders, and studies comparing altered states of consciousness in LSD and other psychedelics. No doubt this unfolding research will help both scientists and recreational consumers better understand this fascinating psychedelic and how to harness its uses.

By providing us with your email address, you agree to Leafly's Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.