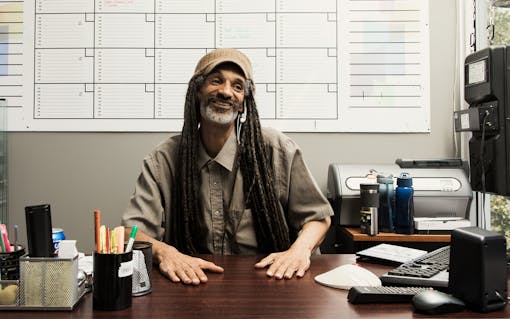

On a Thursday afternoon in June, in a suburb of Vancouver BC, Davidacus Holmes, founder of the Sanctuary of the Rastafarian Order Ministry, Canada’s first registered Rastafarian church, leans forward at his desk, in his corner office, and begins rolling a joint.

He’s wearing a black jacket with the Jamaican flag sewn across the chest and KINGSTON spelled out across the back.

The church is inconspicuous, tucked away on the second floor of a suburban retail strip.

His dreadlocks, currently in year ten of uninterrupted growth, hang over the back of his chair. His computer screen is aglow with a management information system that he built, which houses the details of the church’s members. He logs in under the screen name “Elder.”

From the outside, the church is inconspicuous, tucked away on the second floor of an industrial retail strip in Burnaby, British Columbia, above an auto-body shop and adjacent to a printing and signage store. A residential neighborhood, neutral and suburban, is across the street. Holmes wanted the church to blend into its surroundings, and age quietly, until it’s presence became routine and familiar.

Sacrament kept fresh in Tupperware at the church. (Andrew Querner for Leafly)

The strategy’s worked. In a time when religious affiliation and church attendance is in decline, the Sanctuary of the Rastafarian Order Ministry, which was formed by Holmes in 2012, is thriving. The church, which operates in a city of less than 250,000, has five thousand members and counting. There’s a backlog of applications Holmes is still processing, and each day more people sign up, in person and online.

Across from Holmes’ desk is a block of television screens broadcasting camera feeds from inside and outside the church. Members ring a doorbell to enter, and Holmes pushes off from his desk, wheeling his chair towards the wall, and presses another button that unlocks the front entrance. The melodious belling is constant, seven days a week, to the point that it disappears unless you’re paying attention.

In the church, members receive gifts of cannabis sacrament. There are no retail sales.

In the church, members receive a gift of sacrament (flowers, extracts, oils, and just about anything you can infuse with cannabis, from bath bombs to potato chips) in exchange for a donation. There are no retail sales, and, at the end of the year, members get a tax credit for their philanthropy.

The church is open to everyone 19 years of age and above, and its membership spans age brackets and demographics. Within the church, no doctrine is enforced. People are free to practice as they wish.

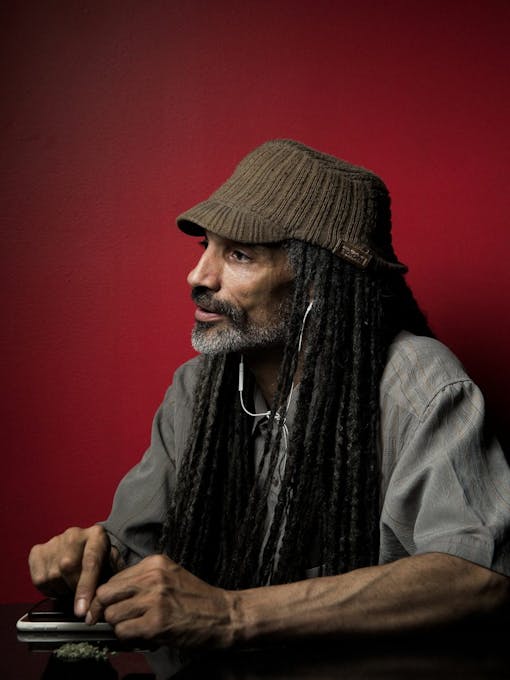

Davidacus Holmes poses for a portrait on the street outside of Sanctuary of the Rastafarian Order, Burnaby, BC. (Andrew Querner for Leafly).

“You don’t have to share our convictions to be our friends,” Holmes says.

This is one of the many dualities at the core of Davidacus Holmes. He refers to himself as a Rastafarian before anything else, and he is knowledgeable and respectful of the faith, and always eager to discuss his religious convictions. Holmes adheres to the 12 Tribes House of Rastafari, which believes in Jesus Christ as the savior and messiah and follows the King James Bible, and he’s the Secretary of State for Accompong, a Maroon village deep in the hills of Jamaica’s Cockpit Country.

Holmes' reverential Rastafarian sanctuary is also, inarguably, a middle finger to the system.

But the church is also, inarguably, a middle finger to the system, a legislative challenge that Holmes is eagerly pursuing, for his personal enrichment, sure, but also to help those ailing with medical problems and to promote sanity around cannabis use and to give back to the community.

“I’ve always had a bit of a problem with authority,” he says, scrolling through church’s social media accounts, ribbons of gray smoke billowing up in the air. “That’s part of being Rastafarian. You can’t be afraid to stand up for what you believe in.”

“Until you go after the Catholic church for not having an alcohol license and serving wine, you can’t come after my sacrament,” he says.

In a filing cabinet next to Holmes’ desk are binders spilling with code and technical information that he’s written. The content management system he’s built to house his membership is thorough and impressive. “I’m the biggest computer nerd you’ll ever meet,” he says.

You can't just approach the Supreme Court and 'ask for something, and they give it to you. It’s government. You gotta fight for it.'

Holmes flies drones in his spare time, he’s Adobe certified, and occasionally he does post-production work in the film industry. He’s also the patent holder for a system of verifying wireless networks and devices, a member of the world intellectual property organization, and the holder of an honorary degree from Oxford.

It’s an impressive list of accomplishments, made greater by the fact that, until he was 35, Holmes couldn’t read. He didn’t finish high school, dropping out when he was 15, after a teacher surmised why he was having so much trouble with his schoolwork: an undiagnosed case of dyslexia. Suddenly, his reading issues made sense, and shortly after that, Holmes left school and began volunteering at an institute for the blind where he could access books on tape.

A member smokes sacrament in the church. (Andrew Querner for Leafly)

Catching a Case Isn’t Easy

Holmes, now 51 years old, is also a tremendous talker, who enjoys a raconteur’s relationship with facts and is prone to launching into soliloquies that weave through philosophy and religion and history and etymology. Among his offerings; never say ‘good morning.’ “Mourning is what you do when someone dies.” And never ask, ‘are you awake? “A wake is something you attend when someone dies. Death is promoted in our culture 24 hours a day, man!” In our time together, it was not uncommon for me to ask one question and still be listening to an intoxicating, expansive answer three hours later.

His career path is also strikingly divergent from his family. He has one sister who’s a judge, another who’s a justice of the peace, and his eldest daughter is an RCMP officer in Ottawa. This may seem strange, because it is, and because Holmes, at this very moment, is trying to get arrested.

“In order to get a religious exemption in Canada you usually have to catch a case first,” he says. It’s exceedingly difficult (and prohibitively expensive) to take an issue to the Supreme Court without charge. The best way in, according to Holmes, is to get arrested first. “It’s not too often you can approach [the Supreme Court], ask for something, and they give it to you. It’s government. You gotta fight for it.”

Holmes is seeking a full religious exemption for the production, processing, and distribution of cannabis. He’s represented by Joseph Arvay, one of Canada’s top constitutional lawyers, who specializes in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and while Holmes is confident he could withstand a legal battle on his own, he knows having such adept co-counsel will only bolster his case. If he receives a religious exemption in Canada, next up is Jamaica and Barbados, and then England. In other words, the church, potentially, has implications for the entire Commonwealth.

It is not uncommon for Holmes’ neighbors to spot a police cruiser in his driveway. He travels to several different correctional facilities across B.C. each week and meets with inmates, from juvenile detention up to maximum security, often to discuss religion, and the officers stop by to inquire about those visits, not to confront him. It’s a strange scene for those new to the neighbourhood: Holmes sitting on his porch, smoking a joint, conversing with uniformed officers, sometimes even offering a toke. (So far, they’ve yet to accept.)

'For Rastafarians, cannabis is a sacrament,' Holmes says. 'It has nothing to do with recreational use.'

Of course Canada’s government has vowed to legalize adult-use recreational cannabis by next July, but Holmes views his cause as outside the volatility and precariousness of that transitional legality. Instead, it’s an issue of religious freedom.

“For Rastafarians, cannabis is a sacrament,” Holmes says. “It has nothing to do with recreational use. It is not recreational. It’s lifestyle. It’s part of our regiment of life.”

He sighs and takes a pull from the joint.

“You’ve gotta fight for it. If you have a grievance or you feel if something is not right, sometimes the only way to fix it is to go to jail and, at the end of the day, not many people are willing to go that far.”

(Andrew Querner for Leafly)

From the Jamaican Hills to the BC Countryside

The church is not Holmes first venture into cannabis. He previously operated two medical dispensaries, iMedikate and 5 Star Organic, where he developed a popular strain called Black Tuna. Black Tuna has some of the highest THC levels of any strain in the world and is known for its sedative qualities—its ability to alleviate stress and depression and induce a tremendous case of couch lock.

Holmes supplies the church with his own product, grown on a farm in the British Columbia countryside. It’s a 50,000 square foot facility, with 15 rooms, each teeming with different strains. Holmes says they use no pesticides or fertilizers at the farm, only structured water. “We’re looking for a higher photonic energy in the water,” he says. “We’re charging the water. If we’re talking from a religious point of view, you’d call it holy water.”

Holmes credits his growing expertise to his Accompong lineage. Accompong is a semi-independent town in western Jamaica, where residents have their own land, their own elections, their own courthouse, and their own laws. “We’ve been growing weed up in the hills of Jamaica for 280 years,” Holmes says. “Because we’ve had that time, we do it a little bit differently than people do it here.”

The 2014 signing ceremony for Holmes’ appointment as Secretary of State of Accompong.

The farm is also the setting for one of Holmes most amazing tales: The Raid. As Holmes tells it, in June 2015, just after 9 am, he went outside for a cigarette. He remembers looking up to see, through privacy slats in the fence, the outline of a tactical truck on the other side. He also saw two men in camouflage, one cutting through the fence, and the second, further away, aiming a gun at him.

The facility, because of its rural location, had to be able defend itself for up to 45 minutes, the amount of time it would take dispatched officers to arrive. With the gun pointed at his chest, Holmes dug his heels into the ground and took off towards the door he had come through. Then, in a perfect Canadian moment, a deer charged and knocked him off his feet.

“I’m flying through the air, thinking how did the deer get through the fence?”

He got his answer when he hit the ground. It wasn’t a deer. It was an RCMP officer with two guns on his back, barrels up, like a set of antlers.

In total, 15 people from the farm were taken into custody, held for four hours, and released without charge. When they regained possession of the farm four days later, the equipment was gone.

Holmes says the motivation for the raid was the fact that the property was nearly entirely paid for by the government, through a federal program that provides tax credits and refunds to these conducting scientific research or experimental development in Canada. (Holmes had received a license to study the packaging of cannabis, and the way he figured it, he could only study the packaging of cannabis if he had cannabis to package.)

A few weeks after the raid, one of the officers returned to the property. Holmes had yet to begin the process of rebuilding, but the discussion with his partners was ongoing. The officer’s visit offered more motivation. He told them that the raid was not personal, that it had cost $300,000, and since they didn’t land a charge, they wouldn’t be coming back. (Holmes asked if he could get this statement in writing, but the officer declined.)

After the officer left, Holmes and his partners sat there for a moment, stunned. Then Holmes broke the silence.

“Fuck it,” he said. “Let’s go again.”

They’ve felt comfortable on the farm ever since.

Cannabis sacrament extract photographed at the Sanctuary of the Rastafarian Order, near Vancouver, BC. (Andrew Querner for Leafly)

Let’s Ride in the THC Mobile

It’s a Friday afternoon and Holmes is backing his car, which he calls the THC mobile—“this thing will never cross the border”—into a parking space at a bank on the outskirts of town.

It’s one of the only banks that will deal with the church, Holmes says.

It’s a warm, sun-drenched day, with a clear sky and steady wind. The car is parked under the shade of a shuddering oak tree, and Holmes, sitting in the driver’s seat, seems drawn to reflection.

“At the end of the day, I couldn’t see many people going through as much grief as I have to prove a point,” he says. “But I know I’m not hurting anybody and I’m supposed to help others in order to help myself. That’s the rule of life. The more time you take for others, the more time you have for yourself.”

Last Christmas, the church donated $15,000 worth of diapers and more than 400 pounds of clothes.

The church is active within the community. One of the organizations it supports is Sheway, a pregnancy outreach program for young mothers. Last Christmas, in partnership with Shoppers Drug Mart, the church donated $15,000 worth of diapers and more than 400 pounds of clothes to the organization. (The partnership with Shoppers was formed after one of their employees joined the church.

Through his relationships at the church, Holmes also learns of local problems that may have otherwise gone unaddressed. One example: the well-intentioned women from a local Christian church that emptied out their coffers to host a fundraising concert with a gospel singer that ended with the church in the red, with a year’s worth of bills still to go. They don’t need to worry anymore.

Then there’s the recently arrived migrant, who, in the safety of Holmes’ office, attempted to sell him cannabis. After a lengthy lecture, Holmes got him a job with his neighbour’s refrigeration company. Finally there’s the church member who I see arrive a few minutes after closing on a Friday night. He finds the door locked and sullenly begins trudging back to his car, when Holmes, who is pulling out of the parking lot, catches a glance of him in his rearview mirror.

“Hey, man,” he says, rolling down his window. “Come here.”

Holmes digs into his pockets and unearths a small bag of sacrament.

“Take this. Have a good night.”

Holmes pulls out of the parking lot, the church member still visible in the rearview, unmoving, unspeaking, frozen, until a smile cracks his face and he begins to laugh.

Davidacus Holmes rolls a joint in the church. (Andrew Querner for Leafly)

Making a Final Delivery

When we leave the bank that afternoon, Holmes steers down a side street, traveling behind a row of suburban homes, slowly snaking between potholes. We pull to a stop behind a house.

“Just going to be a minute,” he says, putting the car in park. “I gotta drop something off.”

He reaches into the backseat, underneath a blanket, and grabs a stack of twenty-dollar bills that’s nearly a foot tall and wrapped tightly with rubber bands. He looks at me, notices my incredulity, and explains with, “Uh…football.” Then he jumps out of the car.

He returns ten minutes later and I press him for specifics. Holmes, in another partnership with a local Shoppers Drug Mart branch, is sponsoring a Burnaby minor football team. The cash will go towards buying the team new equipment and jerseys, covering them for a season. Rather than write a cheque, it’s easier for Holmes to unload some cash.

“The equipment they have is ratty, man,” he says. “It’s gone five or six seasons, it smells like last season’s loser.”

He pulls back onto the road. The sun is still high. “They’ll feel better about playing now,” he says. “That’s my Robin Hood for the day.”

Davidacus Holmes attends to members in the church’s sacrament center. (Andrew Querner for Leafly)