In Canada, legalization grants people the ability to grow up to four cannabis plants per household for personal use—unless, of course, you live in Manitoba or Quebec.

The two provinces have banned adult-use cannabis cultivation at home since the beginning of federal legalization in 2018. A man from Quebec is trying to get the province to reconsider. JanickMurray-Hall is challenging the ban on behalf of himself and any others that may be penalized for growing cannabis at home.

The ongoing legal battle began in 2019 and reached another milestone as the case was heard before the Supreme Court of Canada on the morning of September 15. The hearing took place, as an exception, in Quebec City instead of Ottawa as part of a Supreme Court initiative to make the justice system more accessible to Canadians.

Does a provincial cannabis cultivation ban supersede the rights granted under federal legalization?

Murray-Hall believes that sections 5 and 10 of Quebec’s Cannabis Regulation Act are against Canadian’s charter rights and freedom on the grounds that they directly contravene the federal Cannabis Act. Under the Act, Canadians are permitted to grow and possess up to four cannabis plants per household for personal consumption.

He says that federal law should take precedence over provincial legislation.

In court on Thursday, Murray-Hall’s lawyer, Maxime Guérin, accused the province of creating legislation to “stigmatize the possession and growing and consumption of cannabis,” saying that it undermined the values of the federalact.

“The Quebec government was really looking to offset or counteract the federal legislation,” Guérin told the court as he answered questions from the nine Supreme Court justices seated in the Quebec City courtroom.

Guérin also told the court that the federal regulations “seem to grant positive rights” to Canadians with regard to growing and possessing cannabis plants.

But Patricia Blair, legal representation for the Attorney General of Quebec, told the court that while the federal Cannabis Act may render it not federally illegal to grow cannabis, it doesn’t give Canadians the right or entitlement to do so.

Blair noted that the Criminal Code is not intended to bestow “positive rights,” but to prohibit specific activities.

Blair also stressed that the provincial legislation, including the ban on home cultivation, is intended to ensure the respective safety of Quebec’s youth and its cannabis consumers.

This means that ultimately, according to Blair, the provincial legislation does in fact have “the same objective” as the federal Cannabis Act, despite Murray-Hill’s claims of a disparity.

The court also heard from a long line of interveners, whose role is to advance their own view of a legal matter before the court and to aid in providing a broader perspective on a particular issue than those of the respondents and appellants.

Parties with intervener status included representatives from advocacy groups such as the Canadian Cancer Society, Canadian Association for Progres in Justice, and Cannabis Amnesty; from industry groups such as the Cannabis Council of Canada and Quebec Cannabis Industry Association; and the Attorneys General of Saskatchewan, Alberta, Ontario, British Columbia, and Manitoba, the latter being the only other province in Canada where home cultivation is banned.

Canadians can grow four plants at home—except in Manitoba and Quebec

The legal challenge dates back to 2019 when applicant Murray-Hall, best known for being the creator of the parody website “Le Journal de Mourréal,” challenged two sections of the provincial cannabis legislation that prohibit Quebecers from growing cannabis at home and/or possessing cannabis plants for personal use.

The Superior Court sided with Murray-Hall and found both sections 5 and 10 of the provincial Act to be constitutionally invalid.

In her ruling, Justice Manon Lavoie wrote that the sections infringed upon the jurisdiction of the federal government, which permitted the home cultivation of up to four plants per household and is solely responsible for the legislation of criminal affairs.

Justice Lavoie noted that while the province could potentially place further limits on home cultivation, it could not ban the practice outright. But the decision was overturned in September 2021 by the Quebec Court of Appeal, which unanimously ruled the provisions in question to be constitutionally valid.

Murray-Hall then escalated the battle to the country’s highest court.

Despite overwhelming public support for home cultivation in surveys pre-legalization, growing cannabis at home will cost you. Persons caught possessing or growing cannabis for personal use in Quebec face a fine of $250 to $750 for a first offence, with the amount doubled for a second offence, under the current legislation.

La belle province has long had some of the strictest cannabis laws in the country, including the highest legal minimum age to consume (21 and over), limits on how much cannabis residents can possess in private, and additional restrictions on products like edibles, shirts, bongs, and books.

Manitoba is the only other province in Canada that has banned adult-use home cultivation.

This trial could set the stage for challenging provincial bans in other provinces too

Outside of Quebec, Manitoba residents will be the most directly affected by the upcoming ruling.

A decision that upholds the provincial ban in Quebec would essentially set Manitoba’s own cultivation ban in stone. If the ban is struck down as unconstitutional then many homes in Manitoba may get a little bit greener in the near future, to the likely chagrin of the Attorney General’s office.

For the rest of Canada, the consequences may be less immediately evident in day-to-day life, but Toronto-based lawyer and former NORML Canada director Caryma Sa’d told Leafly that the decision rendered in this case could set a precedent that has legal consequences that extend beyond home cannabis cultivation in Quebec.

A good example of this might be Alberta (Attorney General) vs. Moloney, a 2015 case involving car insurance and a conflict between provincial and federal legislation that has been repeatedly cited by attorneys and in intervener factums as this case winds its way through the court system.

Sa’d says that Murray-Hill’s argument that federal law trumps provincial legislation has some validity and cites the doctrine of paramountcy, which stipulates that in cases where federal and provincial laws are in conflict, federal laws will prevail.

The Societé Québecoise du Cannabis (SQDC) has earned an estimated $168.5 million in net income since legalization and recently announced a net income of $20.5 million for its first quarter ending in June 2022.

The conflict can consist of a direct operational conflict, where it is impossible to comply with both federal and provincial laws, or an indirect operational conflict, wherein the operation of provincial legislation “frustrates” the purpose of federal laws.

But that doesn’t mean that the case is open-and-shut.

“In the name of co-operative federalism, [the doctrine of paramountcy] has to be applied with restraint,” Sa’d explains. The crux of the legal argument comes down to this—does the Cannabis Act actuallygrant Canadians the positive right to grow and possess cannabis plants?

“Yes, I do think that it grants people the positive right,” she says, but cautions that the Justices may not see it that way. “Ultimately, the outcome is impossible to predict.”

Is Quebec protecting citizens or profit margin?

While attorneys for the province and some interveners stressed that the cultivation ban was about protecting consumers and the safety of young people, others have wondered if the province might also be protecting its own financial interest as Quebecers’ only source of legal weed.

In a recent investigation by MJBiz Daily, reporter Matt Lamers revealed that the most profitable cannabis businesses in Canada were, in fact, owned by the government. Number two on the list? Quebec’s own Societé Québecoise du Cannabis (SQDC)—the province’s sole legal cannabis retailer.

The SQDC has earned an estimated $168.5 million in net income since legalization and recently announced a net income of $20.5 million for its first quarter ending in June 2022. With an additional $33.5 million in the form of consumer and excise taxes, the SQDC generated a total of $54 million for the Quebec government that quarter.

“The purpose of the SQDC is not to make profits, but rather a to be a non-profit corporate Corporation,” Guérin said at the end of the hearing, noting that the cash went into “government coffers,” albeit with the stipulation that it be re-invested.

Won’t somebody please think of the children?

The protection of youth was repeatedly cited throughout the hearing, with provincial Attorneys General stressing the ban as a means of keeping kids and young people safe.

But Montreal researcher Kira London-Nadeau, chair of Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy, founder of VoxCann, and a strategic advisor for the national Cannabis & Psychosis project of the Schizophrenia Society of Canada, is skeptical of the province’s argument that the ban on home cultivation protects young people.

“Since the plant needs to be properly prepared in order to deliver any psychoactive effects, growing cannabis at home does not mean youth will have unbridled access,” London-Nadeau told Leafly.

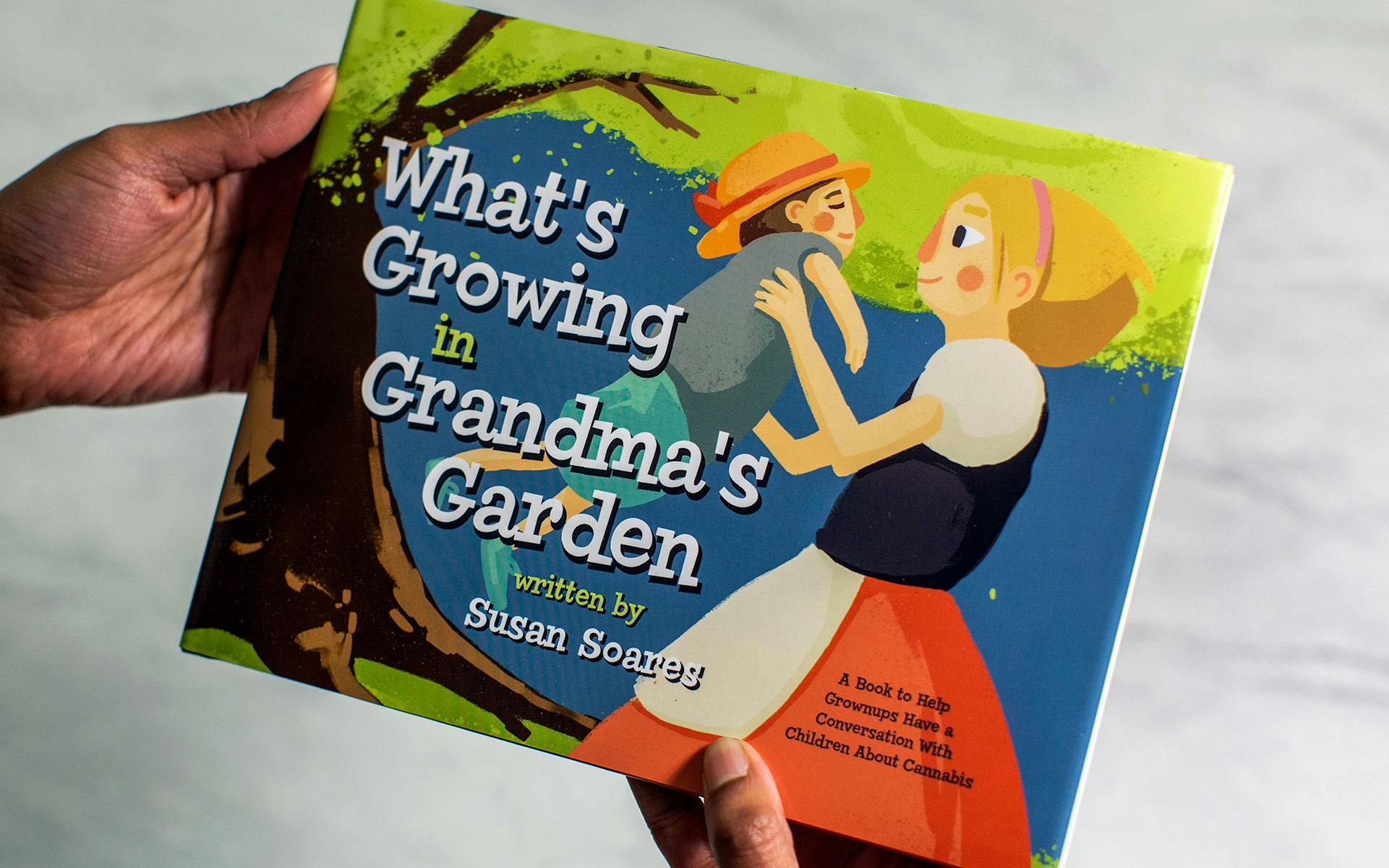

“But perhaps even more importantly, growing cannabis at home opens the door for families to have open, honest and de-stigmatizing conversations about cannabis use.”

London-Nadeau believes that an age-appropriate but straightforward approach is integral when it comes to the safety and well-being of kids and teens.

“We need to do away with the idea that protecting youth means hiding things away from them and take actual responsibility for ensuring that young people have the tools and knowledge to make their own informed decisions,” she says. “This is the best way to support youth.”

Don’t expect to learn the trial verdict anytime soon

When the Supreme Court will rule is anyone’s guess, but Sa’d estimated that it could be months—or longer—before Canadians hear a decision. Until then, home horticulturalists in Quebec will have to fly under the radar to avoid hefty fines.

Alternatively, Quebecers have the option of (illegally) purchasing cannabis products from the illicit market that provincial legislation sought to eradicate, or (legally) purchasing cannabis products from a provincial retailer and handing their money over to the government that enacted the ban.

Regardless of how the Justices rule, it’s somewhat ironic that the province that values its autonomy above all else has lost all decision-making power in its long-game attempt to defend it. With the case now in federal hands, all Quebecers can do is wait.