The world of functional art glass—i.e., beautiful hand-crafted pipes, bowls, bongs, and dab rigs—started out underground, by necessity. But even today, when cannabis itself is legal many places, the scene remains most comfortable in the shadows.

Yes, major art galleries have started to take notice. Yes, some of these bongs go for six figures. And yes, there’s annual trade shows, avid collectors, a few coffee table books, and a killer documentary about this sub rosa subculture.

One thing nobody debates, however, is who deserves to be called the “Godfather of Glass.”

But the real action still takes place in obscure online forums and smoky back rooms, where the scene’s aficionados hotly debate which glassblower or lampworker pioneered or perfected a certain technique, whose art deserves the highest praise, which high-level collaboration proved greater than the sum of its parts, and what hot new talent is currently coming up to change the game.

One thing nobody debates, however, is who deserves to be called the “Godfather of Glass.”

Now, obviously, Bob Snodgrass wasn’t the first person in history to make a ceremonial smoking device. Nor did Snoddy (as he’s affectionately known) invent the glass pipe. By his own account, he first became interested in the form in 1971, when he saw one prominently displayed in the window of a headshop and immediately went inside to inquire about it.

By that point, Snodgrass was already a novice glassblower, and an enthusiastic pot smoker, but he’d never put four and twenty together. Fortunately, on that fateful day, he got to meet the artist who’d made the glass piece in the headshop window. They shared a smoke sesh, became fast friends, and right then and there, our hero had a new calling.

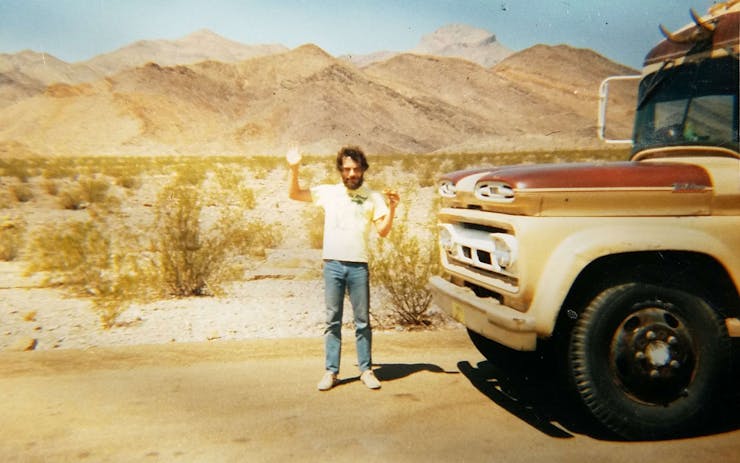

(Courtesy of Bob Snodgrass)

“I’m still primarily a pipe maker,” he tells me, “I also learned to make unicorns and ballerinas and all the other types of tchotchkes you see for sale at the carnival or the flea market, because I was driving all over the country and setting up a table at those kinds of events. And I discovered that if I put out all that other stuff, along with just a few pipes, the people who wanted pipes would always see them, and the people who didn’t want pipes never noticed.”

Snodgrass laughs at the memory, which is nearly 50 years old.

We’re at his family compound in Oregon, which consists of a beautiful old hippie house, a few small outbuildings, and his mobile glassblowing rig (a retrofitted 1940s bus and a semi trailer housing multiple workstations). He’s taking me through the process of making a simple “spoon” pipe from start to finish, explaining every technique and piece of equipment along the way with his legendary charm and kindness.

So Many Roads

(Courtesy of Bob Snodgrass)

Through years of determined experimentation, Bob Snodgrass invented a series of groundbreaking techniques that set his work apart from all that preceded it, most notably “fuming,” which involves vaporizing silver, gold, or platinum in front of a flame to release fumes that then bind to the surface of the glass.

Through years of determined experimentation, Bob Snodgrass invented a series of groundbreaking techniques that set his work apart from all that preceded it, most notably “fuming.”

Fuming gave his pieces an easily identifiable look, especially as it caused his pipes to drastically change color as the glass darkened with use. But rather than clutch tight to this alchemical secret, in order to keep prices artificially high for his output, he instead made a conscious decision to spread this knowledge as freely and widely as possible.

He also invented the popular sidecar style of pipe after spending the night on a friend’s waterbed and finding it impossible to set down his standard pipe on the unsteady surface.

But he possibly contributed the most to the functional art glass scene by selling his one-of-a-kind wares to fellow Grateful Dead fans as the band endlessly toured the country. Traveling with his wife and children, Snodgrass would set up his mobile production studio in the parking lot outside concert venues, drawing a crowd with his lampworking skills while selling enough finished pieces to make it to the next show, and the next, for the next couple of decades.

“The first time I encountered the Grateful Dead scene, a friend told me he had tickets and I should bring my bus so we could camp in the parking lot. He said I was going to sell glass like I’d never sold glass before,” he recalls with an impish grin. “I like to have a theme so I thought of making a little pipe with a Dead Head on the end, and then built up a nice little inventory of those. Well, we ended up working the next two days and nights straight in the parking lot trying to keep up with demand. Meanwhile, I was just blown away by the atmosphere. On the last night I had a ticket, and when I got inside and the music started, I saw everybody just go off in a dancing frenzy. I thought that’s so tribal and I want to be a part of it.”

From then on, the Snodgrass family and their traveling art glass show would be an iconic, benevolent, beloved presence on Dead tour. And that signature piece, designed for that very first show, which portrayed the band’s iconography of a skull in a top hat, became so synonymous with its creator that those lucky enough to acquire one would refer to it, reverentially, as a Snoddy.

Not Fade Away

(Courtesy of Bob Snodgrass)

As the band incessantly crisscrossed the country, the Snodgrass family would return to the same venues and vicinities year after year. Snoddies were only ever sold straight-to-consumer in those days, so his most enthusiastic collectors waited all year to catch him on the Dead lot and pick up a new piece. Often they brought along a friend or two eager to get a pipe of their own.

Over time, this created a market for “heady glass” from coast-to-coast and well beyond. It also gave many future glass artists their first glimpse of how a pipe gets made.

Over time, this created a market for “heady glass” from coast-to-coast and well beyond. It also gave many future glass artists their first glimpse of how a pipe gets made.

“I’ve had many very talented apprentices over the years, but there were also countless people who just watched over my shoulder while I worked in the lot. I let them look through my safety glasses and they understood that you could see through the fire and shape the glass, Really, they discovered that they could learn how to do this for themselves. Some of the best bong businesses in the country got started that way.”

In 2003, a number of those businesses would be targeted by Operation Pipe Dreams—a multi-agency, multi-jurisdictional federal undercover sting operation that culminated in a series of coordinated raids that saw 55 people arrested for crimes related to the sale of “drug paraphernalia.”

Snodgrass believes he was under federal surveillance at the time, but escaped arrest due to good fortune and the fact that he “didn’t have a bank account worth a crap.”

Not that his work wasn’t in high demand.

With a sense of pride and wonder, he tells me he was the first person to ever sell a pipe for $1,000. A deal that clearly went down long before the art glass scene blew up as a way for corporate barons to flaunt their riches.

So I ask The Godfather of Glass how he feels about some of the artists today getting upwards of $100,000 for their most elaborate creations.

“If anybody wants to give me $100,000, I can buy a new motorhome,” he jokes. “And I promise I’ll do my best to make a really, really, really nice piece.”

He says he’s happy for the artists who do so well, and notes that those eye-popping sales allow them to spend a long time crafting a single object, which incentivizes innovation and masterworks.

But it is a little bit of a bummer that most of those head pieces will never be truly functional.

“I make pipes,” he says. “And pipes get smoked.”