In the 1980s and 1990s, lifetime non-cannabis-user Henry Rollins was sometimes aggressively outspoken about his sobriety. After all, he came up in the Washington DC punk scene with his best friend Ian MacKaye, whose legendary hardcore band Minor Threat sang about his personal choice not to drink, smoke, or have casual sex as “having the straight edge”—a term that developed a life and social history of its own.

“While I don't use cannabis, I advocate for its legalization and decriminalization.”

In 1981, when Rollins was 20, his first band State of Alert took a similar stance. “Up in smoke, I laugh in your face / Fucked on drugs, lost in space,” he sang in one song.

From State of Alert, Rollins became the frontman of eminent American hardcore punk band Black Flag, whose dark rage attracted an often hostile crowd, to which Rollins himself became a notorious onstage foil, giving as good as he got. Still, the open antagonism of Black Flag’s shows was exhausting, and that’s when Rollins found himself relaxing his attitudes about cannabis.

“In Black Flag, we had a crazy audience,” he recalls, “but when we were off the road, we lived at the beach south of the airport in Hermosa-Redondo. All of our friends who used to come hang out at band practice, they were all stoners, pretty much. We were loved by stoners. We would play these parties and probably the nicest people I ever met in my youth were at these parties. You know, a nice guy comes up, ‘Hey, man. We know you don’t smoke or drink, so we got you a Martinelli’s juice.’ Someone bought you an apple juice so you can have something to drink! That was so much nicer than the guy spitting his bloody phlegm on my face in Cleveland. How can I have a problem with these people who are friendlier than anyone I meet at my own shows? That’s why by the time I was 22 I’d stowed my contempt.”

Rollins’s support for the end of prohibition comes from personal politics he’s stood behind for decades.

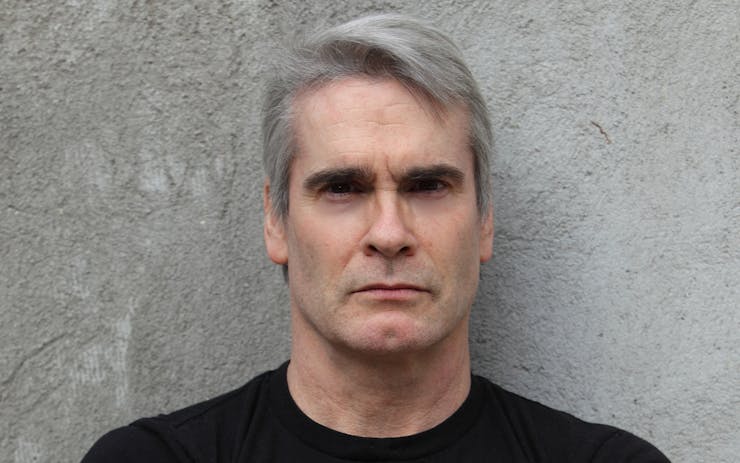

We’re speaking ahead of his keynote address to the International Cannabis Business Conference in Vancouver, occurring on June 25. For those who grew up familiar with Rollins’s hostility to intoxication, it might seem like a strange pairing. But unlike some famously sober celebrities cashing in on the move toward legalization, Rollins’s support for the end of prohibition comes from personal politics he’s stood behind for decades.

“Look at this fake war on drugs,” he says. “In America, cannabis is a way to hurl African American males into prison, which is a for-profit idea. The prison industrial complex is no joke.”

In the 1980s, he learned about the history of the FBI’s COINTELPRO and the widespread use of drugs as a reason to jail Black radicals and other political dissidents. It all added up: drugs, he said, became a clear-cut civil rights issue.

“They’re after brown people and people like me—white people who talk about it,” he says. “The brown, the female, the gay—and I felt I was part of that coming from music. Being in Black Flag, we were easily identifiable by cops. They would let us know that they recognized us. I felt, in a way, ‘You want me gone, too.’ They really didn’t hide that.

A drug conviction, he stresses, was a powerful tool for police to remove dissidents from voting rolls, prohibit those convicted from getting jobs, and get them refused apartments.

“While I don’t use cannabis, I advocate for its legalization and decriminalization,” he says. “This is why. I’ve seen this war on people.”

A Moral Force in a Capitalist Space

In the past few years, he’s spoken at four iterations of the International Cannabis Business Conference and he enjoys being part of the process, acknowledging that his role is primarily as the angel on the shoulder of those attending the convention.

It’s not just the end of the war on cannabis that Rollins is excited about—he’s also eager to see cannabis help people get off opioids.

“Everyone else is onstage talking about being an entrepreneur and how that makes them money,” Rollins says. “Great. If the money is almost a given, don’t let it turn you into a schmuck. To me, if you’re a cannabis dealer, you should see your role in changing the century. When you legalize cannabis in your country, like in Canada, your government is going to have to take on the heavy lifting of what do we do with everyone who’s in jail on a cannabis charge that is now not illegal? You have to retroactively free these people—or not, but you should.”

But it isn’t just the end of the war on cannabis that Rollins is excited about—he’s eager to see cannabis help people get off opioids, and to be used in place of opioids for pain management. The American pharmaceutical industry has been too quick to push opioids for minor pain, he says, when they could be offering cannabis-based medicine instead. Likewise, pharmaceuticals for PTSD might be replaced by medical cannabis.

“Cannabis, to me, is the pushback,” he says. “Your nephew who went to Iraq and came back all banged up, we’re going to help him with cannabis. Your grandma who wants to knit, but her hands won’t let her. We’re going to help with a cannabinoid. The amount of good cannabis can do in this century, it’s going to be the vendors, the retailers, the entrepreneurs who are going to be pushing this out with their social outreach.”

Rollins acknowledges that he’s a little “hopey-changey and tree huggy,” and he’s quick to admit he expects as legalization dawns, there will simply be too much money involved to keep parts of the industry from turning ugly. That’s what brings him yet again to the ICBC: He hopes to be moral reminder to the cannabis industry not to forget the injustice that they came from as they move toward a potentially lucrative future.

“If you just want money, that’s what’s going to make you mean,” he says. “There will be those people who just sell stuff. They don’t care what they’re selling and it’s all about the next houseboat. That’s capitalism and you can’t stop it. Doesn’t mean that everybody has to be that way.”

“Our Job Is to Make Cannabis Like Aspirin”

As optimistic as his vision of the post-legalization world may be, he recognizes that it will take time. Social changes, he says, are almost inevitable provided enough time and education. He cites the long-fought battle for gay rights finally achieving the kind of mainstream appeal that brings RuPaul to primetime television and marriage rights to the White House.

“The gay-rights movement shows that societies can change, and I think cannabis is part of that.”

“It shows you that societies can change, and I think cannabis is part of that,” Rollins says. “It’s right in there with racism and homophobia and misogyny. It’s all about getting information out. I always tell people, you’ve already got a guy like me. You need to hook my dad, who is a tremendous racist, a fantastic homophobe, and a record-breaking misogynist. If he’s still alive—I have no idea. If he’s an old man in his 90s, he might have some knee pain. What if a cannabinoid could help his joints? Wouldn’t it be great to see my dad in line at 9 AM to get into the dispensary and get his chewable, so he can move his fingers? He demonized cannabis in the ‘60s, but in 2018, maybe he uses it everyday. That’s what our job is, to make cannabis like aspirin.”

In closing, he warns again against the impulse toward making as much money as possible, noting big-box products are never as beloved as those made in small batches.

Rollins hopes to be moral reminder to the cannabis industry not to forget the injustice they came from as they move toward the lucrative future.

“You’ve got your mass-produced beer and then you have your microbreweries who make it one drop at a time,” he says. “Cannabis outlets can be like that, where you have your mass-grown stuff that’s like, ew, and then you have the really good stuff made in small quantity. You go to the store and get it from the local guy who grows or supplies really good stuff. If he’s closed, then go to the big box store and buy your enh weed.”

He acknowledges he knows nothing about wine, but he believes those who tell him there’s a difference between the kind that comes in gallon bottles and the kind that’s grown with love.

“Apparently it’s really good,” he say. “You can do that. It’s like the difference between pizza made in New York and frozen pizza from the store. It’s pizza, but one is made by the ton and one is made one at a time. You can have that with cannabis. You’re never going to knock out big money coming into it, but you can have an option.”

Henry Rollins will deliver the keynote address at the International Cannabis Business Conference in Vancouver BC on Sunday, June 24. For full info, see InternationalCBC.com.