Back in September 1978, when Up in Smoke enjoyed its original theatrical run, I was 12 years old—far too young to buy an R-rated ticket. Only in the nicest of dreams might I have slid past an usher, crept behind the multiplex door, and taken in the unfathomable: Cheech and Chong smoking weed on the big screen.

Add in my devout, small-town Ohio ma who may or may not have previously smelled the kind on my windbreaker? Um, no. I had zero shot at hot buttered popcorn accompanying Up in Smoke’s munchies jokes.

The most popular comedy duo of the decade had existed almost entirely outside of television, whose all-powerful censors found their cannabis-infused bits far too risqué for broadcast. Before their first big movie, Cheech and Chong reached their fans mainly on vinyl and eight-track tape. The hippest heads caught ‘em live.

I actually wasn’t able to ingest a Cheech and Chong flick in theaters until 1980, when Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie hit North America. It slayed me. And while I find a lot of Things Are Tough All Over, Still Smokin’, and The Corsican Brothers largely unwatchable, it’s difficult to deny that the six-pack of C&C films serve as a kind encapsulation of the 1978-1984 epoch, when the eighties began emerging from the torpid collective stagger that was America in the late seventies.

Between the ages of 14 and 22, I watched the first three Cheech and Chongs two dozen times. But it’s the original, Up in Smoke, that remains with me—and with American culture. It resonates for reasons I have only recently begun to understand. Don’t get it twisted: It’s common knowledge that Up in Smoke invented the stoner comedy. In its wake would come Pineapple Express, Friday, Half-Baked, the Harold and Kumar series, and other incarnations of the genre.

Up in Smoke pioneered the field. But does it stand the test of time?

I watched it sober and I watched it high. Spoiler alert: High is better.

To answer that question, I screened Cheech and Chong’s debut three times over one month. Still unable to see the flick in a theater, I took it in on iPad and iPhone. I watched it sober and I watched it high. (Spoiler alert: High is crazy better.) I became so immersed in the film that life got to feeling like that thing I did while away from watching Richard “Cheech” Marin and Tommy Chong drive a van made of marijuana from the Mexican desert to LA’s Sunset Strip.

Here’s what this endless lid loop has taught me: Up in Smoke is no masterpiece, not even when I’m way up off that sativa. Still, it’s sorta fantastic, in ways that have a lot to do with enduring art. I love this movie, and it stinks like my old yoga mat.

Remind me: What happens in this movie?

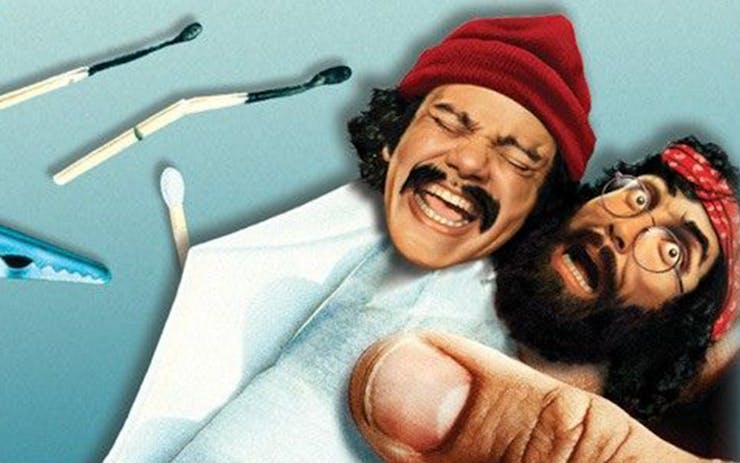

“This stuff will put a hump in a camel’s back”: Tommy Chong, left, and Cheech Marin team up on a quest for some baaad weed. (Paramount Pictures)

No doubt, the plot is as thin as you remember. Cheech is Pedro, a melancholy would-be rock star whose sloppy lechery might be the film’s most dated facet. (Horny stoners are simply more nuanced now.) Pedro hooks up with Tommy Chong’s character, whose name, Anthony, is said aloud only once, at the start. Bearded, bespectacled, and half-Chinese, Tommy plays the classic stellar stoner: powerfully hard to get high.

Misunderstood and questing for ganja, the boys are tailed by an undercover narc. Chaos ensues.

Misunderstood and questing for ganja, the boys are tailed by an undercover narc—an antic and almost unspeakably hilarious Stacy Keach. Chaos ensues.

Straight away: There are parts of Up in Smoke that make ZERO sense. In an early scene on Highway 101, Pedro mistakes hairy-ass Anthony for a lady trying to hitch out of Malibu. Ain’t enough chronic on the planet to get that high. Yet, the unlikeness of the pickup sets a broadness benchmark. This is how we’re doing now. It prepares the viewer for the tub of disbelief that’s got to be suspended to enjoy the 85 minutes that follow.

By the time Cheech and Chong’s characters are guilelessly shaking the LAPD—while driving a van made entirely of weed, bumper to bumper— I was laughing into my iPad and forgiving every plot inconsistency.

That’s not to say the film’s flaws don’t get in the way. Wooden performances from the movie’s supporting players flirt with being too much to bear. At the break into its third act, one realizes that Up in Smoke was a precursor to Purple Rain — a barely-competent film that became fundamental to contemporary culture.

Anyway, give it up for the director

Entertainment mogul and “Up in Smoke” director Lou Adler, far left, sports his usual hepcat style in a courtside seat next to Jack Nicholson at a 2010 Lakers game. (Mark J. Terrill/AP)

Here’s the funny part. This barely-competent film was helmed by one of the giants of the postwar Hollywood scene: Lou Adler.

Long before he became known as The Guy Who Sits Next to Jack Nicholson at Laker Games, Adler was a crucial architect of hippie period pop. He discovered, produced, and managed The Mamas & The Papas and Carole King, as well as a struggling British Columbia comedy duo called Cheech & Chong. That Monterey Pop scene where Hendrix sets his axe ablaze? Adler did that joint. Throw in the ownership role he played in the Sunset Strip nightclub milieu and you’ve got an all-time Hollywood baller.

It didn't take Adler long to figure out that film directing wasn't his bag.

Up in Smoke was Adler’s directorial debut, and it didn’t take him long to figure out that directing wasn’t his bag. (He only helmed one other film, 1982’s Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains.) And should you catch the film, it might take you even less time to come to the same conclusion. But like a good rock-and-roller, Adler kept things moving. Literally. His flick never stays put. Adler filled the screen with classic automobiles, eye-candy on the streets.

Those cars are freighted with symbolism. Before the opening credits hit, Tommy’s character ditches his Westside parental opulence in a Rolls Royce convertible. Cheech picks up the wayward rebel in a 1964 Chevrolet Impala Super Sport. “Anthony” is going on a class ride. When Adler’s product isn’t taking an outrageous side trip to Mexico (played by Yuma, Arizona), the film tends to goofily meander around Los Angeles north of Dodger Stadium, a region some might now call Marc Maron Los Angeles. Here’s where we see Keach’s Sergeant Stedenko rolling with his keystone oppressors in an AMC Ambassador. Unspeakably hilarious.

Cheech, rockin’ that sweet ’64 Impala SS. (Paramount Pictures/giphy.com)

There’s that celebrated minute in which Man & Pedro roll by a Chevy Corvair, a hard-to-find Volkswagen 412, an even more rare Fiat 128 Sport Coupe SL, a 23-window Volkswagen Transporter, and an Opel Manta. The car wrangler threw in a Jaguar E-Type coupe, just for kicks. And then the comedic piece de resistance: A classic ‘70s van made entirely of Acapulco Gold.

Gearheads back in ‘78 must have thrown a rod at this portion of the film. It was inside. You had to be hip. Props to Adler for for his range of knowing nods.

Success threatened the status quo

Charmingly incompetent and eminently watchable, Cheech and Chong’s rapport is where the project’s bread is buttered. It’s peak stoner harmony. Up in Smoke never transcends being a collection of bits, and that’s okay, on account of this rapport. The boys feel at one with the racially diverse urban landscape, and that is peak LA.

'Up in Smoke' made $44 million in theaters, which was major bank in 1978.

Trust that I mean a diverse LA, not Hollywood. (My real ones recognize the difference.) There’s a winking joke about Tommy “getting Chinese eyed,” a nod to Chong’s heritage. It’s dope to be in on that. Pedro, meanwhile, is hella Mexican. His band is basic brown, not market-tested out of believability. And his main ride exudes cholo maximalism. Finally, outside of the film’s crowning battle-of-the-bands scene (at Adler’s own venue, The Roxy), Pedro’s music pays homage to its national roots.

That up-front diversity figured into the movie’s reception in Hollywood. Up in Smoke made a shocking $44 million in theaters, which was major bank back in ‘78. It ranked in the top 15 box office hits that year. Yet, according to Tommy Chong’s biography, Paramount wasn’t interested in making a sequel. From this revelation, it’s right to conclude that the only thing more threatening to Hollywood than minority movie stars were minority movie stars who were zooted and representing for their people. (Feel free to meditate here on the industry’s culpability in America’s xenophobia crisis. Go watch Homeland. I’ll wait.)

Fortunately, other studios were predisposed toward green. By the time The Corsican Brothers (Orion Pictures) spun its final reel in 1984, Cheech and Chong’s six movies had grossed a total of $160 million.

Respect how the comics and Adler took us back in order to move the culture forward: Tommy’s “special joint,” a comically massive J, was vaudevillian in its ridiculous simplicity. Chong’s thang became a prop every bit as iconic as a previous generation’s exploding cigar or squirting lapel flower.

The prop that launched a million J’s. (Paramount Pictures/giphy.com)

As a black male resident of Portland, Oregon, who can purchase legal weed any day of the week, I almost never want to go back in time. So, props are due. I staggered away from my Up in Smoke over-medication with renewed respect for the pioneers. The original stoner comedy is an invaluable document of a time and place when getting lifted wasn’t simple. Reefer Madness was by ‘78 in the catacombs of American movies, yet the real world regarded bud as a menace. Marijuana consumption stereotypes were still beamed into our collective pre-cable consciousness. Dragnet and The FBI gave way to T.J. Hooker and “Just Say No” spots.

Amid the film's engulfing cloud of disbelief, Cheech and Chong were paradoxically real.

Things were tough all over.

Cinema never has and never again will experience a comedic “yes-and” as powerfully seamless as Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong in a cannabis-powered bit. They are Abbott and Costello on Matanuska Thunder Fuck, Seth Rogen and James Franco with the stank of hippie Hollywood all over them. Amid Up in Smoke’s engulfing cloud of disbelief, they were paradoxically real. Real broad. The 8-track legends grokked the value of visual humor, and damn-near did it to death.