The passage of California’s Proposition 215 a quarter-century ago—on Nov. 5, 1996—was nothing less than a seismic event.

Today, as the cannabis community prepares to gather in San Francisco to celebrate the silver anniversary of the first-ever statewide medical cannabis law, we live in an entirely different world—particularly those of us living in places that have more or less followed California’s lead.

Thirty-six additional states now legally sanction some form of medical cannabis. Eighteen states and Washington, DC, have legalized the adult use of cannabis entirely. And while the federal government continues to classify cannabis alongside heroin as a Schedule I narcotic, with the highest potential for abuse and no approved medical use, the days of DEA raids on state-licensed cannabis dispensaries seem to be behind us.

What’s normal today was radical in 1996

One measure of the incredible success of Proposition 215 is that we have begun to take all of the above for granted. But back in 1996, simply protecting AIDS and cancer patients from arrest for growing a plant or smoking a joint that their doctor recommended was a truly radical change. It struck at the heart of a racist and oppressive status quo that at the time appeared nearly unassailable—even to some of the renegades who risked everything to take on the system, and often suffered the consequences.

The history of America’s medical cannabis movement includes a lot of such martyr stories, because despite what you might hear at the next big cannabis business conference, our rights were not secured by the investor class looking to cash in or the political class bending to the will of the electorate.

Safe access to medical cannabis became law in California due to the struggle and sacrifice of a grassroots movement of patients, advocates, and agitators engaged in a sustained campaign of civil disobedience.

Celebrating where it started: San Francisco

On Friday, California NORML will host a conference and afterparty in San Francisco to commemorate the groundbreaking law’s big anniversary.

The celebration features “original sponsors, organizers, medical patients, attorneys and advocates of the Prop. 215 campaign, plus memorials to those who have since passed away and to patients, doctors and caregivers who have been arrested, harassed or imprisoned in the fight for their right to medical marijuana.”

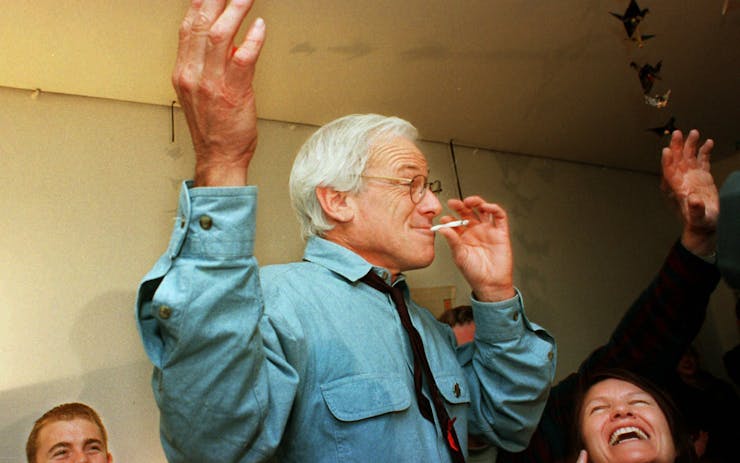

Highlights include a reunion of some of Proposition 215’s co-authors, with California NORML director Dale Gieringer, registered nurse and patient advocate Anna Boyce, and WAMM co-founder Valerie Corral all on hand to share their recollections of drafting the ballot initiative and campaigning for its passage alongside fellow co-authors Dennis Peron, John Entwistle, Jr., William Panzer, Scott Tracy Imler, Leo Paoli and Dr. Tod H. Mikuriya.

The instigators: Dennis Peron and Brownie Mary

It takes many people to make up a movement, but the story of Dennis Peron and Brownie Mary will always be this movement’s starting place. They led a movement that grew out of the desperate need for medical access among San Francisco’s LGBTQ community. And that movement forever changed the way the city, the state, and ultimately the world views cannabis.

Peron discovered cannabis during the war

For Dennis Peron, it all started with his deployment to Vietnam in 1967, where he was pleasantly surprised to find Saigon filled with the sweet smell of weed smoke. A closeted homosexual and a committed pacifist, he worked in the morgue, stacking bodies. Cannabis would prove to be the saving grace of a horrific situation.

When he was discharged in December 1969, he stuffed two pounds of the highest grade cannabis he could find in Vietnam into his Air Force duffel bag and smuggled it to San Francisco. By 1974, he’d parlayed those two pounds into a thriving underground empire that included The Island, a vegetarian health-food restaurant where each patron was greeted with a joint prior to sitting down to eat.

An early advocate for gay rights

Peron was also heavily involved in San Francisco’s push for gay rights, including Harvey Milk’s successful run for San Francisco Board of Supervisors. In July 1977, however, just months before that historic election, the San Francisco Narcotics Squad raided Peron’s operation. During the raid, he was shot in the leg, shattering his femur. He also faced serious prison time over the 200 pounds of cannabis seized.

But after the horrors of Vietnam, Peron always claimed the police couldn’t scare him. In fact, he continued to sell cannabis from his bedside while recovering at St. Joseph’s Hospital.

During a break in the ensuing trial, the officer who’d shot him blurted out a string of anti-gay slurs, and said he’d wished he’d shot him dead. As a result, the officer’s testimony was thrown out of court and the charges were lowered.

Planning a campaign while in jail

Still, Peron spent seven months in prison. While incarcerated, he began planning a local ballot initiative to stop San Francisco authorities from arresting and prosecuting people who “cultivate, transfer or possess marijuana.” It would pass by a wide margin.

San Francisco Mayor George Moscone subsequently instructed the city’s police force to ignore minor cannabis offenses. But then on Nov. 27, 1978, Mayor Moscone and Harvey Milk were assassinated by a homophobic ex-police officer, and the SFPD went back to business as usual.

Elsewhere in the city, Mary Rathbun found her calling

Mary Jane Rathbun was a self-described anarchist whose vocal advocacy for workers’ rights, reproductive rights, and other social justice causes estranged her from her parents and family in Wisconsin. After moving to San Francisco, she married a recently-returned World War II veteran, but the marriage ended in divorce, leaving her to raise their child alone on an IHOP waitress’s earnings.

When her daughter later died in an automobile accident at just 22 years old, Rathburn was bereft, without any surviving family to call her own and often struggling to make ends meet.

Then one fateful day in the late 1970s, she perfected the recipe for some “magically delicious” cannabis infused brownies. Those brownies would make her locally famous in the Castro—San Francisco’s predominantly gay neighborhood—and then turn her into an international cannabis causecelebre.

A brownie becomes a business

Before long, business was booming, with Mary baking several dozen brownies every day to keep up with demand. A grandmotherly figure with curly gray hair, a kind-hearted disposition, and a sailor’s vocabulary, she became a beloved figure in the Castro, serving as a kind of mother figure to countless young people who’d left their families behind in pursuit of a community that accepted them.

Rest assured: Mary most definitely got high on her own supply. Typically she’d eat half a brownie in the morning and then finish the rest in the afternoon. Otherwise, she couldn’t get around too well on her artificial knees, which she earned through a lifetime of standing on hard floors as a waitress.

1980s: A deadly plague hits San Francisco

As the AIDS crisis took hold and devastated San Francisco in the early 1980s, Mary Jane Rathburn noticed that the then little-understood virus vastly disproportionately affected the young gay men she’d taken to thinking of as her children. She also observed that cannabis proved incredibly effective in combating their symptoms and restoring their appetites.

So she began volunteering as a nurse’s assistant.

While making the rounds in local AIDS and cancer wards, she made her brownies available to patients for free. At first she dipped into her Social Security checks to cover the cost, but as word spread of “Brownie Mary’s” kindness and compassion, she began to get donations from altruistic local weed growers.

Meanwhile, across town, Dennis Peron tirelessly advocated for medical cannabis as a compassionate, palliative response to the crisis. He also worked to supply AIDS patients with cannabis directly, in defiance of the law.

If you got a warrant I guess you’re gonna come in

In 1981, the SFPD raided Rathbun’s apartment in a public housing project for senior citizens. The raid yielded 18 pounds of pot, and led to a court date for the 57-year-old edibles impresario.

The case also made national headlines. That spread the message that cannabis was an effective medicine for AIDS and cancer patients, while Rathbun herself presented a sympathetic character and case in the media.

Sentenced to 500 hours of community service, Rathburn volunteered at Ward 86 of San Francisco General Hospital, where doctors, nurses, and staff greeted her with admiration and respect, after seeing firsthand how her brownies brought nausea relief, pain relief, and restored quality of life to countless AIDS patients.

‘I’m going to ask for my marijuana back.’

A year after getting busted, the now notorious “Brownie Mary” got busted again. This time the District Attorney dropped the charges. Not that it satisfied Rathburn.

“I’m not a criminal. I did nothing wrong. I was helping my kids,” she said. “They can’t drop the charges without saying I haven’t done anything wrong. And if they do that, I’m going to ask for my marijuana back.”

In 1986, San Francisco General hospital named her Volunteer of the Year—but that didn’t stop her from getting arrested for a third time a few years later.

Charged with possession of 2.5 pounds of cannabis, she made bail the same day thanks to Dennis Peron, who made sure she emerged from custody to a phalanx of supporters, plus a scrum of reporters and TV cameras.

“If the narcs think I’m going to stop baking pot brownies for my kids with AIDS, they can go fuck themselves in Macy’s window,” she announced to deafening applause.

1990 arrest leads to the first dispensary in America

In 1990, the narcs came again for Dennis Peron. This time ten officers armed with sledgehammers performed a no-knock raid on his home in the Castro. As they searched his apartment for drugs, Peron tried to protect his longterm partner, Jonathan West, who was gravely ill with AIDS. After the raid recovered only four ounces of cannabis, one of the officers put his boot on West’s neck and taunted him with anti-gay jokes. Then they hauled Peron off to booking, leaving his bedridden partner alone and terrified.

West lived just long enough to testify at Peron’s trial. Frail and in obvious physical agony, his story moved the judge to throw out the case and admonish the arresting officers.

Peron seized the moment by co-founding by co-founding (with husband and fellow activist John Entwistle) the San Francisco Cannabis Buyer’s Club. Although he still risked arrest and prosecution, this time he had the tacit approval of City Hall to run a non-profit collective dedicated to supplying cannabis to the seriously ill for free or at a steep discount. The menu featured a wide selection of organic cannabis, plus edibles, tinctures, topicals and health food. In addition to the retail counter, there were plenty of places to make yourself comfortable and share some cannabis with friends or friendly strangers.

A campaign born out of the club

The San Francisco Buyer’s Club also served as a hub for the ascending cannabis movement’s political campaigns. The earliest efforts to draft what became Prop 215 all happened at the Buyers Club, where Peron brought together medical cannabis patients and providers with academics, politicos, and activists eager to join forces on the historic effort.

Here’s how journalist Fred Gardner, who has served as chronicler of the movement, described the political coalition that Peron brought together for Sunday meetings at the first ever dispensary:

Among those who came were Dale Gieringer, the head of California NORML. Valerie and Mike Corral came up from Santa Cruz. She has epilepsy, the result of an accident suffered in the ’70s; Mike had become a grower to develop strains that worked best for her. There was Jack Herer, author of “The Emperor Wears No Clothes,” who had been organizing for legalization since the early ’70s from his home base in Fresno… Pebbles Trippet, a migraine sufferer who’d been arrested often over the years for marijuana possession and transportation… Bill Panzer and Rob Raich, lawyers from the East Bay… Bob Basker, a union man and longtime ally of Dennis’s, and John Entwistle, a closest political confidante… Historian/activist Michael Aldrich and activist Michelle Aldrich… Community organizer Gilbert Baker. Writers Ed Rosenthal, Ellen Komp, and Chris Conrad. Mary Pat and Monty Jacobs Judy and Lyn Osburne, Lynnette Shaw, Dave Bowman, Vic Hernandez… At some meetings, Dennis estimated, there were “almost 100 people.”

Mary Jane Rathbun also played a major role in the campaign to pass Prop 215, despite growing seriously ill in the run up to the election.

“I think I might live to see it, I really do,” she told the New York Times, adding that if California did approve Prop 215, then Governor Pete Wilson, who’d vetoed similar proposals by the Legislature, would “wet his pants, he really will.”

Many hands built a coalition

As time has passed, Denis Peron and Brownie Mary Rathbun have become legends in San Francisco, in California, and among cannabis legalization advocates worldwide.

But as we tell and retell their stories, it’s important to stress that many other activists contributed mightily to building the medical cannabis movement and passing Prop 215.

Remember Dr. Tod Mikuriya

Particular attention should go to the late Dr. Tod H. Mikuriya, the only physician to co-author the 1996 initiative. Mikuriya was a tireless public advocate for the therapeutic properties of cannabis who risked his career and medical license to break the barriers of prohibition.

Also, while the ideas, energy, heart and soul of the campaign came from a core team of grassroots activists, it must be noted that the millions in funding required to collect enough signatures to get the proposition on the ballot and then run a statewide campaign against stiff opposition came largely from a trio of wealthy donors.

It takes money to run a campaign

George Soros, Peter Lewis, John Sperling, Richard Dennis, and George Zimmer all helped bankroll the Proposition 215 campaign, coming in late to assure it made the ballot and then bringing in a campaign team to help promote it.

A dramatic and thuggish miscalculation on the part of the opposition also helped aid the passage of Prop 215.

Just months before voters decided on the issue, one hundred heavily armed police officers raided the San Francisco Buyer’s Club, busting open the front door with a battering ram, in a transparent attempt to intimidate the initiative’s backers and swing the vote against Prop 215.

But the authorities’ oppressive action backfired, pushing many previously undecided voters to support medical cannabis.

Voters approve: Medical marijuana becomes legal

Both Dennis Peron and Mary Jane Rathbun indeed lived to see the day. Prop 215 passed statewide on Nov. 5, 1996, with 56% approval—a huge margin considering that neither the Democratic nor Republican party were willing to endorse it.

Arizona voters also approved a medical marijuana legalization measure in that same election. But the Arizona Legislature quickly nullified the initiative, leaving California to go it alone. It wasn’t easy. The Clinton administration fought medical legalization for years, using the power of federal arrest and prosecution in an attempt to stop, or at least slow, the progress started by Peron, Rathbun, and the voters of California.

For more than a decade, the glaring discrepancy between state and federal law would result in people and collectives operating as authorized by state law getting raided, arrested and imprisoned by federal law enforcement.

Full adult-use legalization would not arrive until 20 years later, with the passage of Prop 64 in the Nov. 2016 election. But ultimately, Prop 215’s significance went far beyond California. It not only freed the state’s patients to find relief without fear of arrest—it sent shockwaves around the world that still reverberate today.