Numerous reports out of San Francisco are confirming the passing of Dennis Peron, 72, the legendary cannabis activist who kindled America’s medical marijuana revolution in the 1980s.

Peron’s brother, Jeffrey Peron, posted this on his Facebook page earlier this afternoon:

“Changed the world” is a phrase entirely befitting the life of Dennis Peron.

Peron was one of the first to realize the health benefits cannabis was offering to AIDS patients.

As a leading figure in San Francisco’s gay culture and cannabis underground in the 1970s and 1980s, Peron was one of the first to realize the health benefits cannabis offered to those battling AIDS in the heart of the crisis that overtook that city in the late 1980s.

Working with other local leaders like Mary Jane Rathbun (“Brownie Mary”) and Dr. Donald Abrams, Peron helped pass an ordinance legalizing medical cannabis in the city of San Francisco, then took the movement statewide with the 1996 passage of Proposition 215, the nation’s first statewide medical marijuana legalization law.

Peron and his husband, John Entwistle, continued to be active in the life of San Francisco over the past 30 years.

Until recently, their bed-and-breakfast “Castro Castle” on the edge of the city’s famous gay neighborhood welcomed all travelers, with day-glow decorated rooms that allowed visitors to enjoy an authentic taste of the city’s psychedelic culture. A painted mural on a garden wall memorialized Harvey Milk, the late San Francisco city supervisor who counted Peron as a close friend and early political supporter.

Vietnam Vet: ‘I came back and kissed the ground.’

The Bronx-born Peron grew up on Long Island in a middle class family. “I looked the same as everyone else,” he told me in a 2014 interview at his home in San Francisco. “I fit in like everyone else. But I just knew I wasn’t that person. Number one, I was gay. I knew I had to hide. Somehow I had to hide. I was a good actor. A good hider.”

'I came home from Vietnam with two pounds of cannabis, and started a career that lasted 40 years.'

That early acquired skill served him well later, he said, when he needed to hide both his sexual identity and his cannabis consumption. “Two for one!” he said.

Peron was drafted in 1966, and served in the Air Force in Vietnam. That’s where he first encountered cannabis. “The people there catered to the GIs. We were a market for them.”

Peron returned stateside with two pounds of cannabis in his gear. “I came back and kissed the ground. I was so happy—partly because I had two pounds with me. That started a career that would span 40 years.”

A Brief Stopover Became a Lifelong Love

Peron stopped over briefly in San Francisco prior to shipping out to Vietnam in 1967. “It was the Summer of Love,” he later recalled. “Perfect timing. Like everyone else, I ate acid and tripped out. The hippies, those people accepted me. I said, ‘I’m going to do everything I can to come back to San Francisco and live my life here.”

Peron tried to join communes, 'but they wouldn't have me. I was too trashy.'

So he did. “I decided I’d be a hippie faggot,” he often said, chuckling, when recalling those days.

Peron applied to join a number of local peace-and-love communes, he said, “but they wouldn’t have me. I was too trashy. I didn’t know who Marx or Lenin were.”

Flummoxed, he started his own commune. “We called ourselves the Misfits,” he said. They lived 25-to-a-house in the Haight. “Bunch of us in a beautiful old Victorian. My brother had a spot in the kitchen, under the table.”

Eventually Peron became one of the city’s flourishing cannabis sellers. San Francisco police busted him any number of times over the years, but Peron usually beat the charge with the help of Tony Serra, the civil rights attorney known for defending the Bay Area’s most famous and infamous citizens.

RIP Dennis Peron, compassionate warrior and champion of medical #marijuana. pic.twitter.com/FVrXT2rS37

— California NORML (@CaliforniaNORML) January 28, 2018

Harvey Milk and the Aftermath

In the Castro’s heyday in the 1970s, Peron’s Island Restaurant served cannabis upstairs, hot food downstairs, and hosted spirited discussions about politics, cannabis, and gay rights in the booths.

In the late 1970s, he was was arrested while in possession of 200 pounds of cannabis—a charge too heavy for even Tony Serra to wipe away entirely. He served a six-month sentence, which was how he found himself in jail on Nov. 27, 1978, when Milk, the city’s first openly gay city supervisor, and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated by former city supervisor Dan White.

“That was the pivotal moment,” Peron recalled. The collective outrage of the city sent a signal to the San Francisco Police Department, which had been notorious for beating and arresting gay men. “They realized they couldn’t keep busting gay guys just because they didn’t like them. They couldn’t bust them, but that didn’t stop them from harassing us.”

Tragedy Strikes the City

Milk’s murder came less than three weeks after the city’s voters passed Prop. W, which demanded that the police chief and city attorney stop arresting and prosecuting people for cannabis. (That didn’t happen. With the death of Mayor Moscone, then-Supervisor Dianne Feinstein took the city’s reins. Feinstein, then as now a fierce cannabis prohibitionist, quashed any further discussion of decrim in San Francisco.)

As the AIDS crisis unfolded in the 1980s, Peron’s neighborhood, the Castro, became ground zero for activists and AIDS patients alike. Peron’s partner, Jonathan West, succumbed to the disease in 1990.

“At that point, I didn’t know what I was living for,” Peron told the Los Angeles Times in 1996. “I was the loneliest guy in America,” Peron recalls. “In my pain, I decided to leave Jonathan a legacy of love. I made it my moral pursuit to let everyone know about Jonathan’s life, his death, and his use of marijuana and how it gave him dignity in his final days.”

The #cannabis legalization movement has lost a great man, #DennisPeron, the co-author of California’s Prop 215 #medicalcannabis initiative and the driving force behind Measure P (the SF local ordinance that preceded it), has died. Rest in peace, Dennis. https://t.co/EzIkOSQ0M7

— Pistil + Stigma (@PistilStigma) January 28, 2018

MMJ Emerges from the AIDS Crisis

Peron and many others in the city knew how their friends and partners fighting AIDS were finding some relief with cannabis.

The anti-nausea effects helped with the chemo treatments for Kaposi’s sarcoma and side effects of many early experimental drug regimes. The appetite stimulation provided by cannabis helped AIDS patients who were fighting “wasting syndrome,” a condition in which people find it extremely difficult to eat and digest enough food to stay alive.

“It helped Jonathan,” Peron later recalled. “He was wasting from 142 pounds down to 110.” Doctors prescribed Marinol, the THC formula in a pill. “Jonathan just vomited the Marinol up,” Peron said. “It didn’t make sense.” A few puffs on a joint, by contrast, did everything the Marinol couldn’t.

Prop. 215 Makes History

In the year after West’s death, Peron threw himself into the cause. He raised enough signatures to put Proposition P, which legalized the medical use of cannabis within San Francisco’s city limits, on the citywide ballot.

In Nov. 1991, San Francisco voters overwhelmingly passed the measure with an 80% vote of approval.

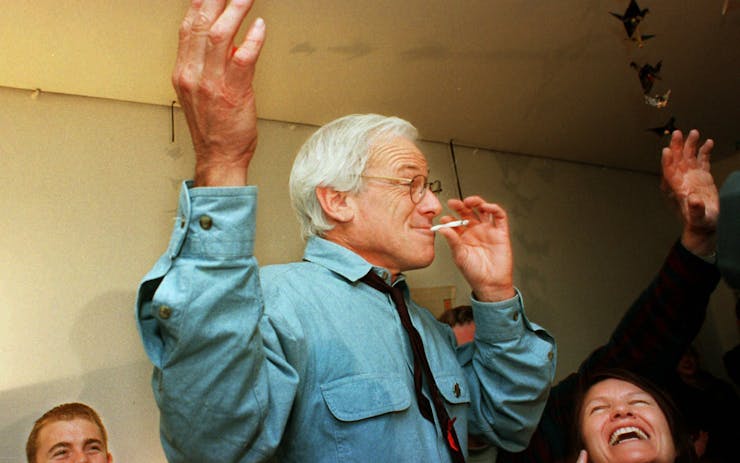

Dennis Peron, takes notes during an interview on the phone, while Gary Johnson lights a marijuana filled pipe in an office at the Proposition 215 Headquarters, formerly the Cannabis Buyers club on Friday, October 11, 1996 in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Peron Robinson)

MMJ Freedom for California

Five years later, Peron and a cadre of allies took a similar measure statewide.

'I knew I had to get everybody' involved in the Prop. 215 campaign, Peron said. 'Clergy, doctors, nurses. I almost had to cut the potheads loose. Too much cultural baggage.'

Prop. 215 faced heavy opposition from powerful political forces, including police agencies throughout the state.

“I knew I had to get everybody” involved in the campaign, Peron later told me. “Clergy, doctors, nurses. I almost had to cut the potheads loose. I had the votes, and they had a lot of cultural baggage that I couldn’t deal with.

“This coalition was pretty forceful. They just wanted change. They didn’t want people to go to jail for marijuana. And if it helped patients, why can’t they have it? Why? We asked that question again and again. We never stopped asking.”

Prop. 215, approved by 56% of the state’s voters, turned California into America’s first state to legalize the medical use of cannabis.

Marriage and Later Years

Peron lived long enough to see his activism vindicated on two fronts. When same-sex marriage became legal in California, he married his longtime partner John Entwistle, himself an outspoken activist on both national cannabis issues and local San Francisco neighborhood politics.

In Nov. 2016, California voters legalized the adult use of cannabis, and the first retail cannabis stores opened a little more than three weeks ago, on Jan. 1, 2018.

In his final months, Peron enjoyed his days with Entwistle in their Castro Castle, which was no longer accepting traveling guests. He was irascible to the end; reporters calling for a quote about legalization were liable to get an earful from Peron or Entwistle about the imperfections in California’s new law. Without Peron, the law would not exist. But that didn’t mean he was done fighting for something better.