This is the first in a four-part Leafly series about legal cannabis in Mexico. Future installments will look at the nation’s roadmap to full legalization, the influence of drug cartels, and how patients can access medical marijuana today.

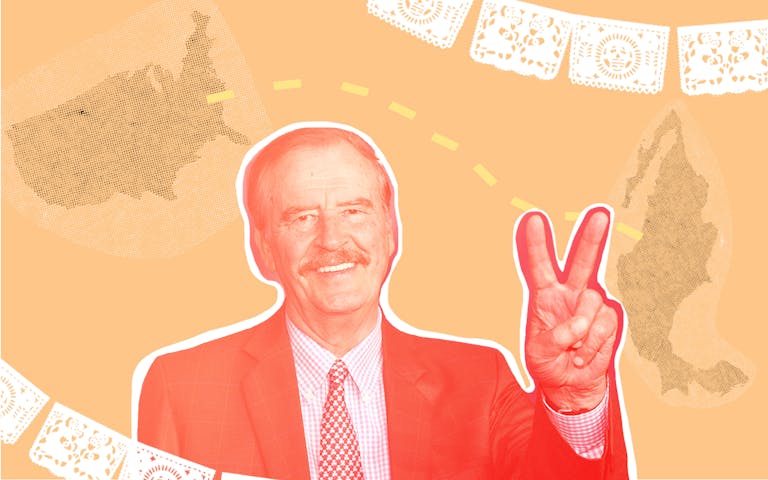

Vicente Fox, El Presidente, delights in being the most talked about Mexican in Donald Trump’s America.

At age 76, Fox may be more familiar to Americans today than when he served as the 55th President of Mexico from 2000 to 2006.

From the moment Trump announced his candidacy in June 2015—by slurring Mexicans who come to the United States—Fox has acted as Mexico’s counter-puncher, needling and mocking Trump via the American President’s favorite medium, Twitter. He celebrates his nation’s refusal to fund Trump’s pet project—“Mexico is not paying for your fucking wall!”—and embraces the imagery of a popular internet meme that depicts him as a badass senior citizen and contender for that Dos Equis crown:

The persona indeed fits Vicente Fox, a towering rancher, former Mexican CEO for Coca-Cola, and ex-governor of the central Mexican state of Guanajuato. In many ways, Guanajuato reflects Fox: devoutly Catholic, with a cowboy swagger and a coarseness of tongue that would make el Papa — the Pope – cringe.

Here near the city of León lies Centro Fox, Fox’s vast presidential library, think tank and cultural retreat. This is where Fox produces his hilariously profane videos pledging to save the United States, a land he loves, from President Trump.

Fox is taking on the greatest challenge of his life: Ending Mexico’s wrenching violence by enacting dramatic drug reform – including full cannabis legalization.

More seriously, this is where Fox is taking on perhaps the greatest challenge of his life: He is crusading against Mexico’s wrenching violence by advocating for dramatic drug policy reform – including drug decriminalization and full-scale cannabis legalization.

It’s a cause that increasingly occupies his mind and his schedule. In the past three years he’s appeared at countless cannabis industry conferences in the US and Canada, urging more reform, faster, now. Last month he even joined the industry, kind of, by becoming a member of the High Times board of directors.

“Fox has been great on this issue,” says Ethan Nadelmann, founder and former executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance. “He has been bold and courageous not just on legalization of marijuana but on ending all prohibition. I think he has had an impact in his country and elsewhere.”

When asked why—Why cannabis legalization, why drug reform, why now?—Fox’s answer is quick and determined. “My main interest is to stop the War on Drugs,” he told me in a one-on-one interview at Centro Fox. “My main reason is to save kids’ lives, to stop the killing and the bloodshed on the streets of Mexico. And that will happen by legalizing – and taking away money from the cartels.”

One Goal: Stop the Killing

Last year Mexico suffered more than 29,000 homicides, the highest total ever recorded in the nation’s history. Most were cartel killings, or cartel-related, including a percentage blamed on Mexican security forces and emerging rural autodefensas, vigilante groups taking up arms against narcotraficantes in place of police.

Mexico’s long, disastrous epoch of violence first exploded in December, 2006, when Fox’s successor, President Felipe Calderón, unleashed the Mexican Army on the criminal networks shipping cocaine, meth, heroin, and cannabis to the United States and other countries. The death toll in 2018 is on pace to top 30,000.

Legal marijuana cuts violence says US study, as medical-use laws see crime fall https://t.co/jnTFNMnzeA

— Guardian news (@guardiannews) January 14, 2018

To answer the begged question: No, Fox has never tried cannabis. This is about politics for him, not self-medication or personal enjoyment.

He is an outspoken international champion for cannabis legalization. Yet his journey may seem contradictory. He vetoed key drug reform legislation as president. And notably, critics assailed him for promising massive reforms to change Mexico’s corrupt political system and then failing to deliver.

Mexico has legalized the importation of cannabis medicine with 1% THC or less. Smokable cannabis is not permitted.

But this is not the Vicente Fox of 2000-2006. This is a fit, active and thoroughly liberated senior, a globe-trotting personality pleased to say whatever the hell he wants, whether in eloquent writings on international affairs or in profane riffs on Donald Trump.

In his sunset years, he is fighting to rescue his country by pushing cannabis legalization as an alternative to chaos and carnage. He tells me he embraces the uncertainly and risk of the cause.

“Every day, we must have a purpose,” he says. “The harder it is, the more complicated it is, the more you’re going to enjoy it.”

Mexico’s Small Steps

Only last year, Mexico approved extremely limited medical cannabis legalization, a tepid step after 90 years of prohibition. Mexico currently allows the importation of “pharmacological derivatives of cannabis” with less than 1% THC. Smokable cannabis is not permitted. Medical products with higher THC levels are allowed only for patients with special government approval.

Mexico currently has no legal domestic cannabis production. Sales of medical marijuana are likely still two years away, as government officials refine the regulations for importing small supplies of medicine from places such as Canada, Europe or Israel—and not, of course, the United States, where such exports remain illegal.

Fox is currently lobbying Mexico’s Congress to do much more. He envisions a flourishing Mexican cannabis industry on par with thriving medical and adult-use economies in many states in El Norte.

And that, he hopes, might begin to put an end to his country’s years of nightmarish violence.

Legalizing cannabis, Fox believes, will stop the bloodshed by taking away money from the cartels.

On a hot and humid morning, Fox and I sat in one of his many offices at the compound. El Presidente relaxed beneath a portrait of him and former first lady Marta Sahagún de Fox, whom he married in 2000 when she was Fox’s presidential press secretary. Elsewhere on the compound, Fox has built an exact replica of his former office as Mexico’s chief executive, complete with windows bearing giant photographs of his past views from Los Pinos, the pine-shaded presidential place in Mexico City.

He began our discussion neither with drug policy or cannabis nor with his nemesis, Trump. He started by talking about his grandfather, the man who made his existence here, on this sprawling hacienda, possible in the first place.

“This is the place where I was born and raised,” he told me. “It’s where my grandfather came back in 1895 without a penny in his pocket, looking for the American Dream.”

Chasing the American Dream in Mexico

Yes, that American Dream. Fox’s German-Irish-American grandfather, Joseph Louis Fox, was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. As a young man, he set out on horseback for central Mexico.

Fox's grandfather migrated from Ohio to central Mexico to raise a family and pursue his dream.

He married the daughter of a French soldier and an indigenous Mexican. He worked as a night watchman in a horse carriage buggy factory and eventually owned the place, earning a sufficient fortune to buy this hacienda, now his grandson’s post-presidential Centro Fox.

It is the headquarters for arguably the most active ex-president in Mexico’s modern history. This is the base for Fox’s policy center and philanthropic organization, Vamos Mexico, which promotes education and nutrition for children in poor, indigenous communities.

This now is also the intellectual bastion for Fox’s quixotic push to address narcotics violence and despair in Mexico. He advocates effectively abandoning Mexico’s militaristic Drug War, for which Fox pins heavy blame on drug consumers in America and international prohibitionist polices enforced by the United States. After so much trauma over so many year, he insists he wants his country back, harmonious and peaceful.

“Today, this place is a think tank, an academy, a place of leadership, love and compassion,” he said of his vast retreat. “This is a beautiful place, where Marta and I are welcoming anyone who is humane and compassionate. This is the place to come. This is the Mecca of happiness and love.”

Curious About Cannabis?Gracias and Get Out

In Mexico, there is traditionally little love for ex-presidents. Vicente Fox is no exception.

Mexican presidents have a habit of leaving office in disrepute. It’s been that way since 1910.

Historically, Mexican presidents have made a habit of leaving office in disrepute. It’s been that way since 1910, when a popular revolt threw out Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, touching off an epoch of turbulence and violence.

In 1929, Mexican governance was consolidated by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (or PRI) and – for 71 years – the party controlled the presidency and imposed a ruthless patronage system that effectively dictated access to political power and wealth. When presidents left office, they were inevitably reviled as villains suspected of enriching themselves through looting the treasury or other forms of corruption.

The stories are virtual folklore: José López Portillo, president from 1976 to 1982, tripled oil production only to crash the economy and dramatically devalue the Mexican peso, which he had pledged to defend “like a dog.” He left office despised, retiring to a vast five-mansion complex secured with suspicious wealth. People dubbed the place “Dog Hill.” Carlos Salinas de Gotari, president from 1988 to 1994, departed amid searing scandal, including discovery of a $100 million European bank account in the name of his brother, Raúl, a mid-level civil servant.

Villas and Swiss Bank Accounts

“Most former chief executives of Mexico do not build presidential libraries (or) crusade against hunger,” Fox wrote in his 2007 memoir, Revolution of Hope. “They generally caught the first plane to Europe, turning over power to a designated successor by pointing the dedazo, ‘the finger.’

“(Then) typically, Mexico’s former presidents exiled themselves to Ireland, drew on their Swiss Bank accounts and hid from the world in walled suburban villas.”

In 2000 it was ‘Fox the Savior’

Vicente Fox was supposed to be the one to change that. In 2000, running as the candidate of the heavily Catholic, conservative and pro-business National Action Party (PAN), he defeated PRI candidate Francisco Labastida by a margin of 46.5 percent to 36.1 percent. Celebrations spilled into the streets. Mexico’s so-called “perfect dictatorship” – the enduring, sinister hold of the PRI – was thought to be over.

With Fox's election, the enduring one-party hold of the PRI was thought to be over.

When Fox left office after his six-year term, ceding power to another PAN candidate, Calderón, he left a legacy of having worked to modernize the Mexican economy through trade deals and globalization. But those policies were seen as harming the poor he sought to help. Worse, he failed to end Mexico’s unrelenting culture of corruption.

Ultimately, he was vilified in the press for lavish spending in constructing his presidential library and retreat, something never seen in Mexico. Pundits wondered whether he had enriched himself in office. Fox asserted he was a self-made man spending his own money, insisting all he took from Los Pinos were his personal belongings, namely, he wrote, “my blue jeans and vaquero belts with the big silver Fox buckle.”

‘He Didn’t Change Anything’

Supporters of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador protest against President Vicente Fox in 2006. Lopez Obrador, a longtime rival of Fox’s, was elected president in Mexico’s national election last week. (Marco Ugarte/AP)

The regal Centro Fox complex, including construction of the posh Hotel Hacienda San Cristóbal, was the least of his image problems. Fox had pledged to change Mexico, to save it, as president. By many accounts, he failed.

“He was an amazing guy who became the figurehead of a democracy movement,” said Benjamin Smith, a professor of Latin American History at the University of Warwick in London. Smith is a leading researcher on the Mexican drug war and political culture. Fox “was a hopeless president” said Smith. “Terrible. Bad. In American terms, he was a blowhard. He had an opportunity in six years to change Mexico, and he didn’t change anything.”

Fox could not reverse Mexico's culture of corruption. But he points to his achievements in improving education and elevating the rights of women.

Fox blames a hostile PRI-dominated legislature for blunting many of his initiatives. Despite his critics, he claims credit for attacking inequality in Mexico by passing budgets that funded scholarships for millions of poor rural children. He changed the welfare structure to elevate the rights of women – other than solely men – as heads of households. He worked to empower teachers’ unions and increase their salaries.

Fox also pushed an aggressive globalist agenda, building on the North American Free Trade Agreement to integrate Mexico into the world economy. He lobbied President George W. Bush on immigration reform and a European Union-style common market for the Americas. He famously got a standing ovation when he addressed the United States Congress on September 6, 2001. Five days later, the United States was attacked on 9/11. New trade deals were dead. Border security was the sudden rage.

The Imperfect President

In his writings, Fox asserts he worked to change Mexico’s pattern of “cronyism, corruption and crisis.” But Mexican scholar and activist Sergio Aguayo, a professor at Mexico City’s El Colegio de Mexico and former head of the Mexican Academy for Human Rights, says Fox notably quit on exposing the corrupt stain of the PRI – thus paving the way for its return to power.

A liberal intellectual, Aguayo embraced the conservative Fox. They met at Los Pinos during the early days of his presidency. Aguayo and other scholars expected Fox to create a Truth Commission to investigate the former ruling party’s Cold War-era “Dirty War,” including the infamous massacre of student protesters in 1968, and the disappearances of more than 1,200 leftists in the 1970s. Fox read the commission proposal and appeared to embrace the idea, which Aguayo saw as essential for restoring democracy in Mexico. But the Truth Commission plan was quickly –and quietly –scuttled.

“It wasn’t taken seriously, and Fox (effectively) became an accomplice with the old regime,” Aguayo told me. “He became one of them. He betrayed all of us who believed he was going to make the change we were longing for.”

Making Allies Across Party Lines

Fernando Belaunzarán, a leader in Mexico’s third major party, the PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution), represents Mexico City in Mexico’s Congress. He’s one of Mexico’s longtime drug reformers, having introduced a bill to legalize cannabis nationwide back in 2012.

Belaunzarán, who joined Fox at the cannabis conference in León, is well aware of Fox’s mixed reputation, including his contempt for the left-leaning PRD. But he’s eager to work with the former president on cannabis reform.

“President Fox is a controversial figure,” Belaunzarán told me. “He was the first president who wasn’t a PRIista. He was criticized because he raised expectations that weren’t fulfilled. But now he is helping in this cause.”

“He took this on after his presidency, when he realized that the consequences of the Drug War had become so grave. He is saying prohibition has been a disaster—and I applaud him for that.”There Are Hundreds of Dispensaries in CaliforniaFox today inspires hope among policy reformers and cannabis advocates with his calls for drug peace in Mexico and creating a legal marijuana industry. But during his presidency Fox proved to be a disappointment to legalization advocates, going along with the same old Drug War policies of the past.

In May 2006, Mexico’s Congress passed a package of drug reform legislation that would have dropped criminal penalties for possessing small amounts of drugs including cocaine, heroin and cannabis. The nation’s cannabis possession limit was to be set at five grams. Fox was expected to sign the bill. At the last minute, however, he vetoed it. “The Mexican government will have to deepen the fight against drug trafficking,” he proclaimed at the time. “In no way is it promoting the use of drugs.”

Critics charged that Fox folded under international pressure, particularly from the drug warriors in the United States. Some 500 protesters held an angry cannabis smoke-in in Mexico City. Similar legislation would be passed again in 2009, three years after Fox left office. Fox’s successor, Felipe Calderón, signed the measure into law.

Forgiving Past Clashes

In our meeting at Centro Fox, the former president defended that 2006 decision, claiming he found the law dangerously vague. It could send people to prison, he claimed, over a distinction of less than a gram of cannabis. “The discussion was over what you could have in your pocket,” he said. “If you had less than the amount, you were a consumer. If you had more, you were a trafficker.”

In the United States, many cannabis reformers give Fox a pass, viewing him as little different than many politicians in El Norte who were prohibitionists in office only to find cannabis religion after returning to civilian life. A recent case in point: former House Speaker John Boehner. An ardent legalization foe in office, Boehner joined the advisory board of a cannabis company last year, declaring his thinking had “evolved.”

“Look, I welcome Vicente Fox’s embrace of Cannabis,” said California cannabis entrepreneur Steve DeAngelo, who joined the former Mexican president at a pro-legalization media event in San Francisco earlier this year. “The more people like Vicente Fox and John Boehner embrace this issue, the more we welcome it.”

Drug War Unleashes a Disaster

Mexican federal police officers escort detained men from a home in Mexico City in 2008. Eleven alleged hit men for the powerful Sinaloa drug cartel were captured at two Mexico City mansions stocked with grenades, automatic weapons and body armor – a day after Mexican authorities reported nabbing one of the cartel’s leaders. (Gregory Bull/AP)

Fox’s caution in office came as narco-violence was building. By 2006, his last year as president, drug-related killings climbed above 3,000. Cartel violence increased notably in states such as Michoacán and Sinaloa, and along the Baja California peninsula. Mexico’s murder rate rose to just over nine killings per 100,000 people. (In 2017, it hit 20.5 killings per 100,000.) But despite his anti-trafficker rhetoric, Fox wasn’t inclined to pull the trigger to escalate the Drug War.

That decision was made, almost immediately, by his successor Felipe Calderón, who dispatched 6,500 troops – the number would eventually rise to 20,000 – in an unprecedented crackdown on the cartels. During the six years of Calderón’s rule, more than 200,000 people were killed. According to a University of San Diego study, Mexico’s homicide rate nearly tripled to almost 25 deaths per 100,000 residents by 2011.

Not long out of office, Fox had an epiphany. He concluded that prohibition and the escalation of Mexico’s drug war had unleashed a humanitarian disaster.

“He (Calderón) thought it was going to be an easy action and, in six months, Mexico would be back in order,” Fox told me. “Nothing could have been further from the truth.”

As the carnage ebbed and then rose anew under President Enrique Peña Nieto of the PRI, with cartels currently battling for spoils after the arrest and extradition to the United States of the infamous narco kingpin Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán, Vicente Fox set off on a world tour promoting drug reform and cannabis legalization. Those events are only part of a rigorous schedule of paid speeches and appearances, an average of 45 a year, on international issues, also including protecting human rights and the environment. Fox says he donates earnings to support Centro Fox and Vamos Mexico programs.

AMLO: A Fox Rival Takes Over

Now Peña Nieto is on his way out. Former Mexico City mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the new National Regeneration Movement party (MORENA) swept into power in a landslide July 1 election.

López Obrador is perhaps Vicente Fox’s most hated rival. Fox compares the president-elect to the late Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez. López Obrador has suggested granting amnesty for narcotics offenses as another path out of Mexico’s Drug War. But cannabis reform was largely ignored in the race. The president-elect has been noncommittal on the issue, saying only that it is an issue “worthy of discussion.”

“Politicians in Mexico don’t want to talk about this,” Fernando Belaunzarán told me. “But it is conversation in our living rooms.”

Move Faster, Now

Fox told me the day before the conference that he hoped to “get rid of the fear…that legalizing marijuana is the devil.”

“I want to move ahead in the process,” he said. “I want the decision makers to move faster.”

The event drew a few Mexican congressional members and heads of government agencies that regulate medicine. Those agencies are currently drafting regulations for the forthcoming medical cannabis sector, which is expected to be heavily restricted and rely solely on imported medicine.

“In this moment, let’s share our points of view,” Fox told the gathering. “I want to be able to say that Centro Fox has a plan for a productive industry, a sound industry, a legal industry. This would be a great change for humanity.”

Fox is under no illusion that cannabis legalization alone can wipe away all the bloody footprints of narcotics violence. But he believes it’s the absolutely necessary first step.

“There has been too much blood, too much criminality, too much delinquency,” he told the conference. “Centro Fox is proposing solutions. Let’s take this plant and its processes and study them. This is a great phenomenon. It’s a transformation.”

Big Idea: Add Cannabis to NAFTA

Vicente Fox speaks during a news conference on the first day of the U.S.-Mexico Symposium on Legalization and Medical Use of Cannabis in 2013. Fox calls himself a soldier in the global campaign to legalize marijuana, and he foresees a day when the marketplace will deliver an array of benefits from sharply reduced cartel violence in his home country to new jobs and medicines. (/Mario Armas/AP)

Fox works best with big, bold, brash ideas—ones that he himself won’t have to implement. Case in point: Last June, at the International Cannabis Business Conference in Oakland, Fox called for an amended North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that includes a new accord allowing for cross-border flow of regulated, legally-produced cannabis between Mexico, the United States, and Canada. In October, he told the Southwest Cannabis Conference and Expo in Phoenix that “prohibitions don’t work – they have never worked.”

Fox’s pro-business outlook isn’t lost on DeAngelo, director of Oakland’s Harborside dispensary and the California cultivation venture, FLRish.

“Fox is one of the leading voices in Latin America on cannabis reform, perhaps the loudest and most vocal,” he said. “And he comes from a business establishment that has not always been supportive.”

But business is what Fox knows—it’s the environment in which he’s thrived. He’s not by nature a political radical. In business, he rose from driving a truck for Coca-Cola to heading the company’s Mexican division. Quality products, well-known brands, and national distribution networks—that’s Fox’s wheelhouse.

Last February, the cannabis entrepreneur Marco Hoffman, found himself sought out by El Presidente at a Seattle cannabis conference. Hoffman is CEO of Evergreen Herbal Distribution, a state-permitted cannabis company with a 44,000 square-foot production facility in the state of Washington.

The former president was fascinated by the cannabis industry experience of the much younger Hoffman, whose firm produces cannabis sodas named HighDrate, Stoney Mountain and Blaze.

“We communicated about the lineage of Coca-Cola,” Hoffman recalled. “And then he said, ‘We need a guy like you to come to Mexico.’”

Trump as a Comic Foil

Fox’s cause is drug reform and a peaceful end to the cartel wars. But his current fame is due largely to his ability to poke and prod the bull up north—Donald Trump.

In Fox’s eyes, Trump is an unprecedented antagonist who poses a real threat to Mexico-United States relations on immigration, drug policy and many other issues.

Candidate Trump’s infamous slur against Mexicans during his June 2015 Trump Tower campaign kickoff (“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” Trump declared. “They’re sending people who have lots of problems and they’re bringing those problems. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists and, some, I assume are good people. But I speak to the border guards and they’re telling us what we’re getting.”) angered and emboldened one Vicente Fox Quesada. He told me that Trump is appealing to “white supremacists who don’t want brownies” in America.

Fox took to writing about Trump as a scoundrel, a con man spewing “America First” rhetoric in the same spirit as corrupt PRIistas used to rail about the “evil American empire” to the north, while silencing political dissent in Mexico.

In his recent book, Let’s Move On – Beyond Fear and False Prophets, Fox likened the nationalistic populism of Trump with the nativist socialism of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. He writes: “I am no longer president of Mexico, but I have dedicated the rest of my life to working for social justice and democracy and to opposing hypocrisy and fraudulence of popular demagogues.”

But such pearly political writings aren’t what is making Fox a cult hero. It’s that “fucking wall” thing, Fox’s assault on Trump’s purported $30 billion “racist monument.” Particularly, his profile has lit up with Fox’s Trump-trolling YouTube videos – produced at Centro Fox, complete with goats and Mariachis. They are making him a septuagenarian rock star.

Last September, Fox announced his satirical candidacy for president in 2020 with a message for Trump from his replica Los Pinos office:

“Donald, every time I make fun of you…people say, ‘Why can’t you be our president?,” he begins. “America, I feel your pain. We all do. And that is why today I am proud to announce my candidacy for president of the United States.”

A goat enters, strapped with the sign: “Vicente for Presidente!”

“Now, I know, a lot of you will say, ‘How can you be president?” You’re a Mexican,” Fox continues. “And to those people, I have three worlds: Donald Fucking Trump. If that worn-out baseball glove tightly gripping a turd can be president, then, amigos, anyone can!”

Sergio Aguayo, an unsparing critic of Fox’s presidency, finds important humor and purpose in his Trump trolling. He calls it a morale boost needed by many Mexicans.

“I’m glad he is raising his voice because we have a president who isn’t,” said Aguayo, who depicts outgoing president Peña Nieto as too timid in his reluctance to push back against Trump. “I think there’s been a policy of appeasement.”

For his part, Fox calls the videos “marketing, pure marketing” to disseminate a larger message. His feelings run deep. He believes fully in the righteousness of his crusade to legalize cannabis, and he will defend to his final word the honor and dignity of his fellow Mexicans. But he also acknowledges the place of joy and humor in the human experience. “You must have some fun,” he told me. “And in 76 years of life, I have.”