LOS ANGELES — Though people of color were hit disproportionately hard by the war on drugs, California’s new legal cannabis industry is overwhelmingly white. And while a handful of cities in the state have already introduced social equity programs designed to give a leg up to those hit hardest historically, a new bill in Sacramento could expand the effort to all corners of the Golden State.

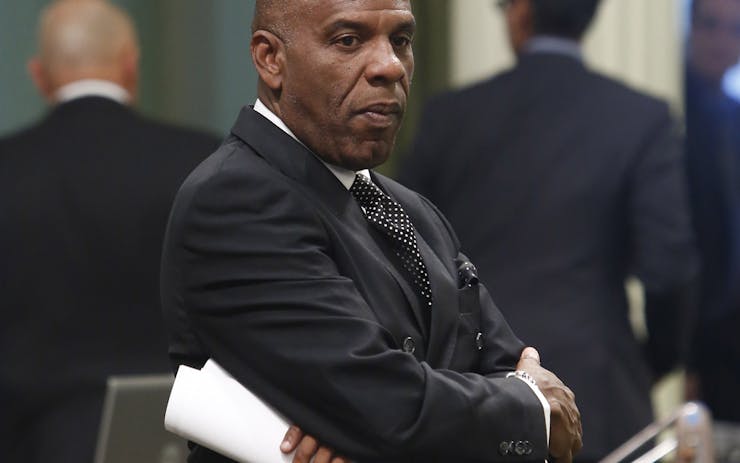

Introduced by state Sen. Steven Bradford, who represents Los Angeles-area neighborhoods including Watts, Compton, and San Pedro, SB 1294 would require state cannabis regulators to create a program to “ease the burdens associated with obtaining a state license and participating in the cannabis industry.” People from communities that bore the brunt of the drug war could gain access to job training, compliance assistance, and help securing capital.

“California’s emerging cannabis industry has the limitless potential to contribute to our local and state economies,” Bradford said in a statement, “and also help stimulate and redevelop communities that were hit hardest by marijuana criminalization.”

“SB 1294 will reduce the burdens and barriers faced by individuals who were once punished by a system of harsh drug laws, but are now attempting to enter the legalized market.”

Under the proposed bill, which passed the Senate Business, Professions and Economic Development Committee on Monday, the state Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC)’s resulting equity program would provide technical support to applicants, offer reduced licensing fees or waive them altogether, and implement an incentive program to encourage other cannabis businesses to work with or hire equity applicants, according to the text of the bill.

The Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development, meanwhile, would be required to help equity applicants and licensees through different forms of funding, such as grants and reduced-interest loans.

Financing is often one of the biggest barriers to entry into the cannabis industry. With this in mind, the bill also proposes that $10 million be allotted to back small businesses within state or local equity programs.

“SB 1294 will reduce the burdens and barriers faced by individuals who were once punished by a system of harsh drug laws, but are now attempting to enter the legalized market,” Bradford said. “This bill is also about people of color that may already have the resources to enter the industry, but have faced racial discrimination, which excludes them.”

Titled the Cannabis Collaboration and Inclusion Act, Bradford’s self-described “first statewide cannabis equity bill” presents a number of unanswered questions, presumably to be addressed by the task force it would create. For example, it’s not clear how the state program would work alongside existing municipal equity systems or who precisely would be eligible.

Reached Wednesday, Ryan Morimune, the senator’s legislative director, said that neither he nor other staffers had been authorized to speak on the record about the bill.

Many of California’s major cities already have such ordinances in place. Sacramento, Oakland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles each has implemented—or is in the process of developing—social equity programs tailored to the local community. Qualifications for these programs are typically tied to an applicant’s income, neighborhood of residence, and whether they’ve previously been arrested for a cannabis-related crime.

For instance, to qualify for Oakland’s program, which opened to potential licensees in May 2017, an applicant must be an Oakland resident who either has a prior cannabis conviction or has lived for 10 of the past 20 years in a neighborhood that saw an exceptionally high number of cannabis-related arrests. Applicants also have to make 80% or less of the city’s median income, which in 2016 was $80,400 for a four-person household.

While the particular qualifying factors can vary based on a city’s population, supporters say the need for these social equity programs is universal and stems from decades of disproportionate policing and punishment of minority communities. In Los Angeles, for instance, black residents made up just 9% of the city’s total population between 2000 and 2017, yet they accounted for 40% of cannabis-related arrests, according to LAPD data.

Gathering similar data on the state level seems to be a priority under Bradford’s bill, which requires the Bureau of Cannabis Control to begin issuing annual reports on cannabis convictions and their broader impacts.

“California has always been a national leader on many issues,” Bradford said, “and while we are not the first state to legalize the recreational use of cannabis, we can be the first to do it right – by including people of color, those with diverse backgrounds and individuals who have been most impacted by marijuana criminalization.”