It’s been a messy couple of years for cannabis politics in Maine.

Out here in the easternmost state, we have a reputation for political independence. That’s partly because Democrats and Republicans have equal numbers, so indie voters often determine the outcome of elections. But it’s also a result of the first law of Maine politics: Geography is more important than party.

Political issues are filtered through a “Two Maines” lens blurred by jealousy and history. The populous coastal communities are seen as relatively prosperous, busy with tourism, restaurants, and desk jobs. Northern Maine, by contrast, is full of land, trees, and poverty. The reality of the situation is more complicated, of course, but for the most part, recent voting trends show the south leaning very liberal and the north mostly conservative.

Cannabis law reform, interestingly, doesn’t seem tainted by this Two Maines bias. Probably because the state’s entire population loves to get high.

A 2014 debate at South Portland high school about whether voters should legalize marijuana. At left, Edward Googins, chief of police in South Portland, and David Boyer, the Maine political director for Marijuana Policy Project. Photo via Getty

Okay, that’s a slight exaggeration. There are rumors of a couple folks who don’t vape, eat, or toke cannabis, but I’ve never met them. For almost five decades, Maine’s rural inland, far from the summer crowds of the shore, has benefited from a thriving underground cannabis economy. Abandoned farms and clandestine forest gardens were gold mines meeting a never-ending demand for “Maine Green Bud” by urbanites from Portland to Boston to New York. In central and western Maine, south-facing mountainsides and hills clear-cut by lumber companies became primo growing locations due to scant police presence and plenty of sun.

More valuable than lobster, potatoes, or blueberries, it’s no secret that rural Maine has survived, in part, thanks to the fall cannabis crop. Before the rise of trimming machines, seasonal $20-an-hour scissor jobs weren’t hard to come by. Countless mortgages and tax bills have been paid with harvest cash. “Weed money” has financed Christmases, college educations, and plenty of cars and trucks. Every town in Maine seems to have a head shop and/or grow store. All through the summer, there are dozens of music festivals and events where cannabis liberation is encouraged and allowed.

More recently the state’s well-regarded, seven-year-old medical marijuana program has spawned thousands of legit jobs across Maine, most notably in regions slow to recover from the Great Recession. That’s probably why the state’s bombastic Tea Party governor, Paul LePage, has been unusually quiet on the issue.

LePage and others may soon be forced to take sides, though, as Mainers will finally have the chance to legalize and regulate adult-use cannabis use this November.

Getting there hasn’t been easy. The road to a legalization vote has been fraught with in-fighting, backroom deals, foolish mistakes, and knuckleheads. In other words, very Maine.

Paul McCarrier, president of Legalize Maine and co-author of the Act to Legalize Marijuana. Photo by Tristan Spinski

* * *

In the beginning, there were two competing legalization campaigns.

Legalize Maine — mostly long-time, long-haired activists and growers — got to work first, introducing an initiative written to guarantee the rights of backyard gardeners and ensure that small-scale farmers benefited from prohibition’s end.

A couple months later the suit-and-tie wearing Marijuana Policy Project (MPP) began pushing their own model. Their initiative called for more stringent regulation and allowed large corporations to dominate Maine’s proposed marketplace. The MPP plan also included stricter penalties than those currently in place for possession of more than an ounce.

Legalize Maine and MPP spent most of 2015 as sworn enemies, each disparaging the other’s proposal, intentions, sartorial style, and matriarchal lineage. When dueling autograph collectors hit the streets, voters became confused about the measures. (“Didn’t I already sign this?”)

Campaign manager David Boyer passes a box of petitions to Rep. Diane Russell from Portland on Feb. 1, as the Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol prepares to deliver the petitions to Augusta. Photo via Getty

Money decided the issue. MPP could afford to pay signature gatherers, but its corporation-friendly measure lacked the grassroots support required for guaranteed electoral success. Legalize Maine founder Paul McCarrier had the backing of the backwoods, but he lacked the cash necessary to fully finance the signature campaign.

Finally, last October, after a series of secret meetings, the two groups announced a truce. The agreement was simple. The wording on the ballot initiative would be identical to Legalize Maine’s homegrown language, but MPP would name and run the campaign and pay for the politicking. Everybody emerged happy. The activists were relieved of fundraising responsibilities, and MPP was more than willing to compromise on language and bankroll a possible victory to further its cannabis street cred.

It should have been smooth sailing from there, but of course it wasn’t.

In February 2016, the combined campaign delivered 21,000 petitions containing 99,229 signatures to Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap, predicting widespread support at the polls in the fall. “Most Mainers agree it is time to end the failed policy of marijuana prohibition,” said MPP’s David Boyer. “And they will have the opportunity to do it this November.”

A month later, organizers were stunned when Dunlap announced he had disallowed more than 47,000 signatures because of alleged irregularities by several notary publics involved in the effort.

David Boyer, campaign manager for Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol, in the organization’s headquarters in Portland. Photo by Tristan Spinski

Legalization supporters around the nation were dumbfounded. Nearly all petitions have a certain percentage of names disallowed for one reason or another — but not half.

Here in Maine, however, the mention of a single name brought instant recognition and understanding: Stavros Mendros.

Mendros is a former Republican lawmaker who now owns Olympic Consulting, a signature-gathering company based in Lewiston. Mainers know him primarily for his 2007 conviction on three counts of election fraud. In late 2015, MPP hired Mendros and his company to supervise petition processing for the legalization campaign. It was a shocking display of political naivetc. MPP was either unaware of his previous troubles — or didn’t care.

Mendros’ involvement ensured, of course, that the petitions touched by his company would be severely scrutinized. And they were. Of the 47,000 initially disqualified, Secretary of State Dunlap voided 17,000 solely because he thought Mendros’ signature notarizing the petitions didn’t match the one the state had on file.

Once again, MPP’s deep pockets came to the rescue. The group filed suit to appeal the decision. One month later, Superior Court Justice Michaela Murphy overruled Dunlap, saying his actions were a “vague, subjective and/or unduly burdensome interpretationi of election law. She ordered the petitions to be re-reviewed. They were, and this time enough signatures — the campaign needed at least 62,000 — passed muster. “The Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol will go before voters in November.

Staff and volunteers for the legalization campaign are sort petitions at an office in Falmouth, Maine. Photo via Getty

* * *

Despite the bumps along the way, the referendum’s chances are looking good. According to MPP’s latest poll, about 55 percent of Mainers favor taxing and regulating, a slight increase over a March 2016 poll by the Maine People’s Resource Center, which pegged support at 53 percent.

In light of the almost 300 fatal overdoses connected to opiates and heroin last year, the public is finally becoming aware that pills are the real problem and no longer believe the reefer madness malarkey. These days, everyone knows somebody helped by medical marijuana. In 2014, Portlanders passed a local, albeit weak, ordinance legalizing possession. That doesn’t mean statewide passage is a sure thing, though.

In drafting the measure, Legalize Maine knew they needed support—and votes—from more than just recreational cannabis users. That’s why most of the 10 percent sales tax on legal cannabis is earmarked for school spending. Maine’s landowners, whose property taxes fund the state’s educational system, are likely to be happy with that feature.

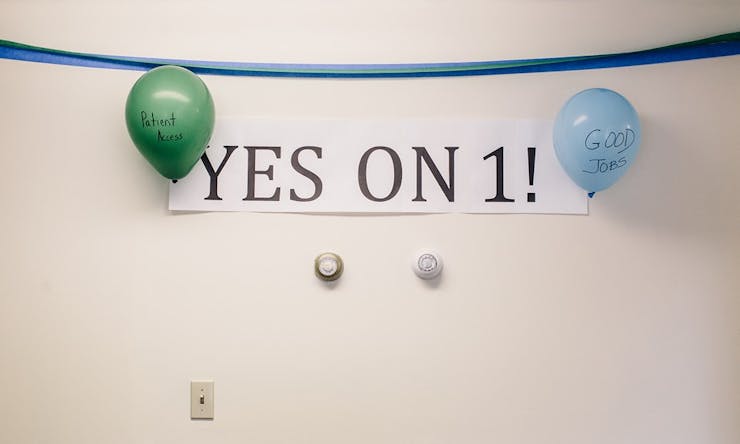

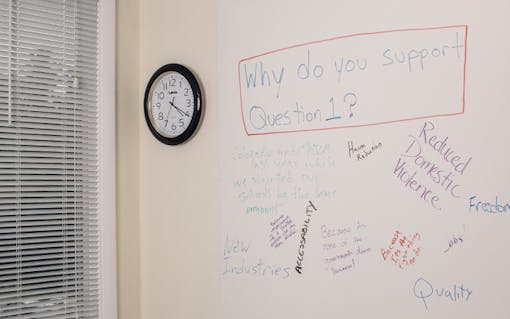

The Campaign to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol’s Portland, Maine, headquarters. Photo by Tristan Spinski

To quell potential concerns from the established medical cannabis community, the proposal clearly protects the state’s established medical program. That provision convinced a board member of the Medical Marijuana Caregivers of Maine (MMCM), a trade group representing small-scale legal growers, to endorse the measure. (MMCM itself has not officially endorsed Question 1, though. “We are trying very hard to only work on expanding and protecting the medical program,” MMCM Board Chair Catherine Lewis explained. “We have members on both sides of the fence.”) Dr. Dustin Sulak, a Maine physician internationally active in medical cannabis research and treatment, has also endorsed the measure. Many lawmakers and activists are also urging a yes vote as a way to head off the corporatization of cannabis.

It’s become apparent to most in the Maine marijuana movement that this referendum is the best and possibly only chance to legalize before the Legislature, the feds, and big business get their sticky fingers in the pot. Plus, savvy growers realize marijuana tourism is where the real profits linger, so it’s important to beat Massachusetts in the race to legalize in the East. Maine is more vacation-friendly than Massachusetts, and Maine-grown ganja is tastier and far more potent than the stems and seeds Massachusetts will try to market. Imagine a cannabis-infused Maine lobster feed, complete with corn, clams, and blueberry pie, versus a Fenway Frank, a bag of chips, and a warm, cheap beer.

Scott Gagnon, campaign chair for Mainers Protecting Our Youth and Communities, an organization concerned with the potential social impact of cannabis legalization in Augusta, Maine. Photo by Tristan Spinski

Still, there are local pockets of resistance. The clunkily named “Mainers Protecting Our Youth and Communities” is led by Scott Gagnon, a longtime substance abuse prevention expert. He hasn’t released the names of any supporters, but his website, Not On My Maine Street, appears to contain a lot of copy-and-paste material from Kevin Sabet’s “Smart Approaches to Marijuana” site. Gagnon’s fundraising efforts so far seem to consist of a $5,000 GoFundMe campaign currently stalled out at $215.

A handful of medical marijuana doctors and caregivers are also in opposition, worried that legalization would cut into their profits, and they’re joined by a small, slightly paranoid wing of the state’s cannabis community, which is still bitter over Legalize Maine’s partnership with MPP. The disgruntled group’s trouble with the measure is more conspiratorial than concrete, and its activism has been so far limited to social media and a protest mounted outside Legalize Maine’s office-opening party last week.

The Portland, Maine, headquarters for the Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol campaign. Photo by Tristan Spinski

Behind the scenes, activists aren’t too concerned with the cranks and the confused. They believe straightforward education leading up to the vote will convert the cautious. Then it’ll be time for the real work: implementing the new law and making sure politicians don’t screw it up during legislative review.

Crash Barry has written extensively about Maine’s cannabis culture. He’s the author of the true story Marijuana Valley and the gritty memoir Tough Island. He adapted his novel Sex, Drugs and Blueberries into a full-length film of the same name. He lives in western Maine near a marijuana grove.

Correction: The original version of this article stated that the Medical Marijuana Caregivers of Maine endorsed Question 1. The group has not officially endorsed Question 1, and the article has been changed to accurately reflect the group’s position.

Image and header image by Tristan Spinski