For Ramirez, his family, and many other Americans, the War on Drugs was simply a ‘war on us.’ Here’s how he beat the odds, and what he plans to do now that he’s free.

There are still thousands of non-violent cannabis prisoners in the United States.

With recreational cannabis now legal in 19 states and Washington, DC, and medical marijuana legal in more than half of U.S., something isn’t adding up.

President Joe Biden and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy ran on promises to free and forgive these prisoners. And they’ve delivered some victories, including 9 non-violent cannabis offenders being granted clemency by the president in April. But both Biden and Murphy still run administrations that criminalize the plant.

While state governments and licensed sellers finalize billion-dollar plans to legalize, current and former prisoners are still carrying the weight of unjust enforcement and sentencing. The new industry sprouting before them only compounds the pain, which trickles down to families and communities who are still blocked from joining most of the brave new weed markets opening across the nation.

‘I’m still a prisoner’

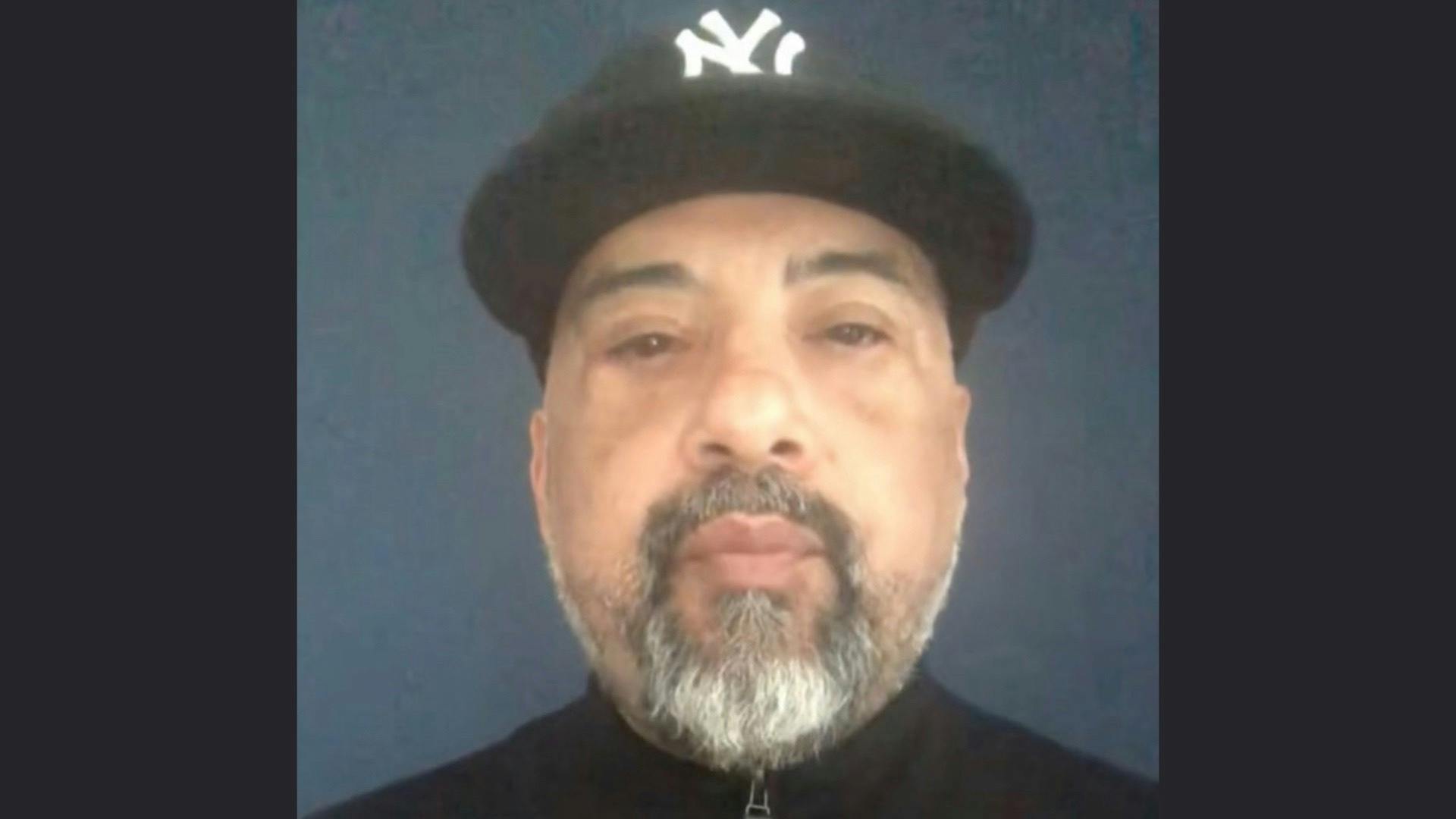

The juxtaposition of legal weed is especially striking to Humberto Ramirez, a New Jersey native who was watching the state’s new cannabis market boom from behind bars until last Friday (September 16).

Over a series of phone calls with Leafly earlier this year, Ramirez and his partner Brooke Popplewell shared their experience as victims of America’s failed War on Drugs. They also shared their hopes to run a legal cannabis business one day soon.

Leafly spoke to Berto and Brooke again this week to welcome him home. Read Humberto and Brooke’s first-person accounts of his incarceration and release below.

Finally home, but so far to go

“This weekend, we went back to our normal routine. Did yard work and went food shopping together… The smile on our daughter’s face was priceless. But I’m sure it’s gonna take time and him getting (used) to being home, because he is very quiet right now.”

Brooke Popplewell

“When he came home on Friday, I picked him up and there was a bunch of people there who helped on his case. We went to a luncheon, so he didn’t say he was overwhelmed, but I think he was a little bit because he’s never met these people.”

Brooke Popplewell

My name is Humberto Ramirez

My loved ones call me Bert. I’m from Cape May County, New Jersey. But right now I’m in a Kintock state prison in Bridgeton.

In 2019, two weeks after New Jersey voted to legalize cannabis, I was sentenced to seven years (two minimum) after I was stopped by police with six pounds of cannabis. I’m up for parole in November.

In April, they let the state’s first dispensaries start selling legal weed to all adults. In month one of sales, seven corporations brought in $22 million from over 200,000 legal transactions.

“I think it’s very disheartening that we get to watch the whole world celebrate marijuana and enjoy themselves. And my family was literally torn apart for a nonviolent crime. Our daughter’s father is no longer home. He’s a father of three children. People can walk into a store and buy marijuana right now but we haven’t been able to see him in over a year. Because of COVID, we have not even been able to hug him.”

Brooke Popplewell, partner of Humberto Ramirez

That’s my partner, Brooke. She’s been supporting me through this entire thing. If I get access to a phone, I call her every afternoon. The past few months, I haven’t been able to call as much. That’s because I tested positive for COVID a couple times. The last time I had to quarantine, I was found unconscious with a head injury from dehydration. When I’m not on lockdown, I’m still in a cage for 23.5 hours per day.

Quarantine is basically like lockdown. When we test positive, we get sent to a different facility in Crosswicks, New Jersey, not far from the state capitol building.

A few miles from that cell, politicians are in the state capitol building patting themselves on the back, calling the legalization of cannabis in The Garden State a huge success.

Watching it all happen from here doesn’t feel like a stoner’s dream for me and my loved ones. The dream that legalization represents for so many smokers still feels like more of a nightmare.

How Brooke and my lawyers helped get me out

“He could have been home a year ago in April 2021. I had two paid lawyers. And the Last Prisoner Project lawyer wasn’t hired to review the directive that actually got him released. He was hired to work on the clemency from the governor. While we were trying to get clemency last year, the New Jersey Office of the Attorney General issued a directive that revised state guidelines on mandatory minimum sentences in nonviolent drug cases. The goal was to ease sentences in the future, and for current inmates. But a lot of prosecutors are ignoring it.”

Brooke Popplewell

“So I hired a second lawyer to help us with this directive. Everyone kept telling me Berto doesn’t qualify for the directive. I’m not a lawyer, but I read that thing like five times. And I’m like, he absolutely qualifies. Nobody would listen to me at the time. If they did, he would have only done six months instead of two years.”

“I met an attorney named Jeffrey Hoffman in New York when I was at a Last Prisoner Project event. He connected me with a former Mercer County public defender named Kathleen Redpath-Perez. She actually left the public defender’s office because of the way that they treat people. Now she works for the Law Offices of Eric A. Shore. But the corruption that she’s seen is what forced her to leave. So it was really because of her. She got the prosecutor in Berto’s case to admit in writing that he was wrong.”

Brooke Popplewell

“Come to find out, the other lawyer that I hired is friends with the prosecutor in Berto’s case. I think they all were in cahoots together. The prosecutor is not responding to people who were supposed to be released across the state. But my new lawyer Kathleen went directly to the Attorney General’s office. It’s not up to the prosecutor’s discretion were their exact words. This is a directive that every prosecutor in the state of New Jersey should have followed suit, but many ignored… It’s going to free a lot of prisoners when we get the word out.”

Brooke Popplewell

Here is a link to the directive that helped free Humberto. On April 19, 2021, Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal issued a statewide directive to law enforcement instructing prosecutors to waive mandatory parole disqualifiers—commonly known as mandatory minimum prison terms—for non-violent drug offenses.

“We found out he was coming home in April. And then maybe like a month and a half ago we got the release date… We got the judgment of conviction changed in a world-record time. They actually changed it in like 24 hours. Then you have to wait 42 days before you can come home so that they can notify victims. Even though there were no victims in this case, it’s a standard across the board.”

Brooke Popplewell

How I started smoking weed

When I was young, it was a fun thing. And then after I got older, it helped me deal with anxiety, depression, and just to stay focused.

The ’90s, we had kinda good weed. You wanted to get Chronic, cause of Snoop. But you’re not getting chronic back then. You’re getting regular, Arizona. And every now and then, some shit called hydro would come around every now and then. That was pretty much the best you could get back then.

My favorite strain of all time is Sour Diesel. And I like OG Kush. Pretty much any kind of Kush. I know this is Leafly. But I’m not really technical when they come to weed. I just smoke. But I also like GSC and Green Crack.

As an adult, cannabis was like my therapy after work. Brooke never smoked with me. But her parents did. She was cool with me smoking in the shed or in my man cave. I started getting pounds to keep my expenses low. I would supply friends and family at a low price or for free.

“The last time I smoked pot was 2003 in college. I haven’t done it since, but I always knew that Berto did. He’s not a drinker. He’s just a very sedentary, good person. He honestly would give pot to my dad, who’s suffering from cancer. And my grandmother, who can’t afford her chemo.”

Brooke Popplewell

7 years for 6 pounds

February 19, 2019, I was 43 years old. I was driving my Dodge Charger in Middle Township, New Jersey, when police stopped me and searched the trunk. I could have gotten a pre-trial intervention program. Then I wouldn’t have to serve time. But I had two prior convictions from when I was 18 and 20 years old. I made it almost 25 years staying out of trouble. Now I was facing two minimum, seven max.

When I was 18, it was cocaine. That’s what I started selling. I wasn’t selling weed. I just went straight to the hard route. You couldn’t tell me nothing back then. I was trying to get rich. A lot of those young dudes were into the gang life, but not me. I was going hard trying to make money.

Nothing violent, though. I have no violence on my jacket. I always told myself I would never do something violent over drugs because that’s what they bought them over here for. For us to kill each other. So if I got mad about stuff in the streets back then, I would just move on.

“When I graduated high school, I went to the military office and tried to apply. The guy told me I didn’t qualify ’cause I had charges at the time. That right there is what made me the angriest person in the world. Something in my brain just clicked and that’s it. I was like, ‘If I can’t help my country, I’m not gonna destroy the country…’ So that’s the route I took and I went hard with it, 100%. Couldn’t tell me nothing. Not, my mom, my dad, nobody could tell me nothing. That was the beginning of the ’90s. The end of the crack era.”

Humberto Ramirez

Punishing ‘just us’ is not justice

Even back then, we knew what the War on Drugs was really about. Richard Nixon said it himself. Joe Biden and the Clintons did, too.

So in 2021, when New Jersey gave a directive to rescind all mandatory minimums for nonviolent drug offenders, there were 32 people in Cape May County who had already been sentenced, me being one of them.

“They let 16 out immediately. All 16 of them were Caucasian and had heroin or methamphetamines. None of them had weed, and Bert’s case had to go to review. They prolonged it so long that the attorney general took a new position. And all of a sudden they’re saying that this law can’t be applied anymore. At this point the lawyers say our best bet is a clemency campaign to the governor.”

Brooke Popplewell

Cape May’s Middle Township Police Department reported in 2020 that its Street Crimes Unit made eight arrests and seized $925 from the sale of substances like cannabis and synthetic weed. Somehow, I was one of those eight.

“Even the judge (Joseph Levin) could see he made a bad decision as a kid, and he was still paying the price for it. He didn’t wanna send him the prison. Those were his exact words. He took out the book. He was licking his fingers, trying to read things. And the prosecutor, a young ambitious lady, she just wasn’t having it. She kept saying, ‘Under statute, yada yada, yada.’ I wanted to ask her, woman to woman, ‘Are you a mother? Because no mother wants to take a parent from their child who hasn’t actually hurt anybody.'”

Brooke Popplewell

Growing up in New Jersey

My cousin and my mother, they were originally from Puerto Rico. They moved to Vineland, New Jersey first. But my mother always said Vineland was like the country. So when she later moved to Wildwood, she loved it. She always wanted to live the city life. She grew up in the country in Puerto Rico.

That’s how I ended up in Wildwood, New Jersey. Ninety percent of the students in my graduating class were white. It was technically a nice place, but I went through racism every day until I left in 2001. The police out there, they’re the worst, like, really prejudiced. I can see their hate. I can smell it. ‘Cause I’ve been through it my whole life. So I’m kind of used to it. But I’m not prejudiced at all.

‘Not in my backyard’

Even with the people of NJ voting for legal weed, conservatives in these smaller areas are blocking weed companies from coming to their towns.

In New Jersey, you can go right over to the next town and your reality will be completely different. Like, I got a saying: You make two right turns in Wildwood, they’re pulling you over.

“You don’t see the amount of racism that actually takes place until you’re in the same home with someone dealing with it. I watch him go in stores, local stores that he has been shopping in. He’s from here, his whole life, and they follow him around. I’ve watched.”

Brooke Popplewell

These local municipalities are very powerful. The state votes blue overall, but many of these towns are very Republican. The towns we’ve lived in are a perfect example. Middle Township, you have one mostly Black area in it. Whitesboro, that’s where my family is from. But if a Black person drives through the Crest in north Wildwood, you’re getting pulled over. You better not even cross the bridge.

“If you’re a white person in the underground cannabis trade, and you do business with people of color, it become clear pretty quickly the disparity in cannabis enforcement, and the punishment… That was evident to me, from the beginning. I had a childhood friend, he didn’t do anything that i didn’t do in the way of selling cannabis. But he got busted. They would handcuff him, they would take him down to the station, they would process him, and they would take him to juvie hall. So my friend ended up not being able to get a job anywhere other than the local strip club… When the cops would come up to me, it would be ‘Alright kid, empty the baggie out, get out of here.'”

Steve DeAngelo, Last Prisoner Project founder on Cannabis Lab podcast

Trauma that trickles down

Before my incarceration, I never missed a school meeting, dance, recital, or competition. I was the only dad in the dance team carpool. I did and will still do anything to take care of my daughters and Brooke.

I’m stuck in a room all day, but Brooke is really suffering, too. Her father just finished chemo and had his bladder removed. She works around the clock. I used to be there to help with all of that. So I feel like she’s stuck doing 20 in a maximum security out there.

“I believe that we should have prisons. I’m not that type of person. He did make a poor decision and yes, he does have to pay the consequences. But someone in Bert’s situation should be on house arrest. He is taking accountability for what he did right now. I’m taking accountability for what he did. Our children… It’s Christmas time. We don’t get to see ’em, you know, the whole thing sucks.“

Brooke Popplewell

Brooke is so bothered by this that she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Her doctor even recommended she try medical cannabis. That’s why it’s so crazy to see it be legalized and applauded.

What it’s like to watch the plant become legal

I saw how much they sold so far and just had to shake my head. I don’t know what Gov. Murphy is up to. But how can you legalize something before dealing with all of the people who are still locked up for it?

Brooke Popplewell

“If he was in front of me, I would ask Gov. Murphy to take a look around. The amount it costs to house them, the people that are suffering at home. I’m a nurse. I’ve had to work through the pandemic and be a single parent… Cannabis is not something that kills anyone… And now people make millions of dollars off of it. But minority families go down for it. You’re leaving single family homes. So the children suffer. The spouse suffers. And of course he is. Everyone is completely suffering.”

It felt hopeless to me, to be honest. But Brooke found some help by contacting the Last Prisoner Project and other lawyers for me. She said she didn’t expect them to write back. But LPP founder Steve DeAngelo and his team have come through so far.

“They are what I refer to as my earth angels. And they’ve all been so supportive. I can message anyone on the team at any time. They’ve given me hope.”

Brooke Popplewell

How Last Prisoner Project is helping

So far, LPP helped us financially, and with my commissary for food and books. The lawyer they hired has been more efficient and helpful than the two Brooke had to pay for herself.

In an interview, the founder of LPP said he’s been incarcerated, so he knows what it feels like. And that he has a lot of friends, some who are still incarcerated to this day. He said he’s not gonna stop until everybody gets full freedom out of this legalization deal. The governor and the president should both talk to him. Maybe he can get through.

“I grew up at a time and in a family where if you see something wrong, then your job is to stand up and fight it. I fell in love with the plant immediately, and was not willing to be a criminal for the rest of my life… So it led me to being an activist. For me to be happy in this world, I had to make cannabis legal.”

Steve DeAngelo, Last Prisoner Project founder on Cannabis Lab podcast

What I will do now that I’m home

The Last Prisoner Project said they are going to help me get a dispensary started. That’s what I’m basically focused on. And I’m planning on getting my commercial driver’s license and driving a dump truck to make money outside of that.

Hopefully I get work with a good company, so I can get a good offer, the perks, the benefits. I get a good job, good paying job with good benefits. I’m sticking to that. I don’t just want to do my own little thing ’cause there’s a lot that comes with it that I don’t know yet. So I’m gonna start crawling first.

And then me and Brooke both decided we’re going to help with any type of advocacy that we can for other people like us. It would feel great to send letters, help a family with Christmas gifts, and way more.