Shannon Hattan is the co-founder and CEO of Fiddler’s Greens, a California cannabis tincture maker, and as an entrepreneur she should be feeling great. Her ten-person company, based in Santa Rosa, got one the first adult-use licenses to grow cannabis in the state. Fiddler’s award-winning products are on hundreds of store shelves. The company is quickly approaching profitability.

Instead, Hattan lives every day on edge. She emptied her 401(k) and plowed all of her late parents’ retirement savings into transitioning Fiddler’s Greens, a former medical cannabis collective, into a licensed adult-use company. She and co-founder Cameron Hattan, her husband, work 100-hour weeks without pay.

“We’ve seen a lot people who were really good at what they did get pushed out.”

The Hattans need to raise $5-7 million for expansion, but Shannon is too busy complying with onerous state regulations to take meetings with investors. At this stage of the company’s life, a small business loan or line of credit is what makes the most sense for Fiddler’s Greens. But because this is cannabis, bank loans are not an option. If Hattan were to even raise the possibility with her own local branch manager, she might lose her checking account for mentioning cannabis.

Meanwhile, some of her competitors are rolling in money. They don’t have bank loans—they have several hundred million dollars in investment capital to burn. They can afford to take losses for years as they gain market share.

“We’ve seen a lot people who were really good at what they did get pushed out—and I don’t think we’ve seen the worst of it.”

“Those with the most money get the most toys.”

A pernicious dynamic has emerged in legal cannabis: Costly states regulations, combined with a lack of access to small business bank loans (due to federal prohibition) is de facto redlining all but the richest 1% out of legal cannabis.

If nothing changes, Hattan says, “I think we end up with three or four homogenous [national] brands.”

“The strong will survive,” said Dana Chaves, senior vice president and director of specialty banking services at First National Bank in Florida. First National offers basic banking services (but not loans) to several Florida medical cannabis businesses. Chaves testified during a Congressional hearing before the House Small Business Committee in June. “Those with the most money get the most toys.”

What Was and Is Redlining?

Most folks probably think of redlining as something from the past, but they’re wrong.

In the 1930s, New Deal-era federal bureaucrats rated depressed American neighborhoods for credit-worthiness. They colored the riskiest areas in red on maps. Those red areas were usually inner-city neighborhoods where people of color lived. Over generations, private lenders used those credit maps to deny home and business loans to people of color.

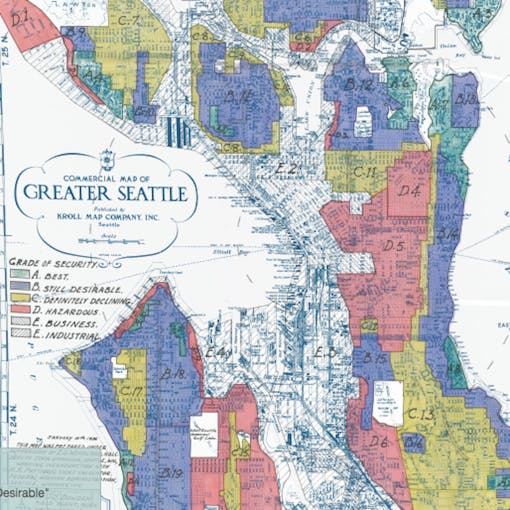

For example, here’s an actual 1936 redlining map of Seattle, produced by the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, part of University of Richmond’s Mapping Inequality project.

Blue and green areas were considered good investments. Yellow and red districts were labeled risky, and people wanting to buy homes there would have a much harder time obtaining home loans. (via “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed July 19, 2019)

Redlining led to Civil Rights-era reforms in’ the ’60s and ’70s that banned race discrimination in bank loans. Federal officials reached redlining settlements with banks in 2015 for $30 million, and 2016 for $200 million. But the effects persist. Black wealth, per capita, is 9.5% of whites in 2019, partly due to the inability of black families to pass down wealth created through real estate ownership.

“We’re still dealing with the effects of this, 50 years later,” said Shanita Penny, president of the board of directors of the Minority Cannabis Business Association.

Today, because no banks offer business loans to any company operating in the legal cannabis industry, personal wealth—or access to it—is the number one thing you need to start a legal cannabis company.

Small Is Out, Big Is In

It’s perverse, but cannabis prohibition was once one of America’s most successful small business programs.

The threat of arrest and incarceration boosted cannabis crop prices ten-fold to a peak of $5,000 per pound in the late 1990s, enriching growers. Police couldn’t go after everyone, so they targeted the largest-scale producers. As a result, a multi-billion cottage industry of smaller operators flourished after California legalized medical cannabis in 1996.

That’s gone now. California opened its legal adult-use cannabis system in 2018. With prohibition waning, prices are collapsing, margins have thinned, and profits come from large-scale growing and sales.

Adult-Use Licenses Cost $2M and Two Years

Ask any restauranteur or contractor—it’s hard to start a small business in America. But it’s ten times harder to start a cannabis business.

US cannabis industry revenue is to set to grow from $11 billion in 2018 to more than $23 billion by 2022. Illinois’ adult-use market is scheduled to launch on Jan. 1, 2020. Florida’s medical cannabis industry grew by more than 700% last year. Nevada’s adult-use market is surging.

But opening a cannabis shop is not like opening a lemonade stand. It’s more akin to high-end urban residential real estate development. Experts say it can cost $2 million and two years of time to get an adult-use license in a state like California. And that’s on the low side. Sometimes it can cost up to $5 million.

To be considered for a license you have to lease and hold a building or storefront for months or even years. Application and licensing fees can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. You might need pricey lobbyists and consultants to help you win permits. Building out your farm or store costs hundreds of thousands of dollars more. Then you have to pay for personnel and inventory. After you’re open, plan to lose money for at least a year as you build up a customer base.

That’s a lot of capital. And there’s not a bank in the nation that will consider you for a loan.

Why Banks Won’t Make Cannabis Loans

US banks had $618 billion in outstanding loans to small businesses in 2016. They’re a major source of funds for startups. But none of the cannabis industry’s growth can come through small business loans from banks.

Federal prohibition creates too big a risk to lenders, explained Dana Chaves at the First National Bank in Florida. Several hundred small banks and credit unions around the country handle basic services like checking accounts and payroll for licensed cannabis business, in exchange for massive fees. First National Bank serves many small independent businesses, but no bank will give a cannabis business loan, she said.

“They will turn you down,” said Chaves. “They won’t even look at you.”

That’s because property is often used as collateral for a small business loan. It’s the bank’s safety net if the borrower defaults. Not so in cannabis. Federal prohibition means a US Attorney can attempt to seize the property of any cannabis business, under asset forfeiture law, at any time.

“It is a big risk,” said Chaves. Speaking from a banker’s perspective, she said: “We have no safety net on our end.”

While traditional small businesses might be able to tap a federal Small Business Administration loan program, or state small business program, those aren’t generally available in cannabis. A few states like California and Massachusetts, and cities like Oakland, have nascent programs for small or minority cannabis businesses. They are rare exceptions, not the rule.

Tap Personal Wealth, Relatives, VCs, or Fold

With small bank loans off the table, small cannabis business operators have to get very resourceful, said Penny. They can try to bootstrap the business by tapping retirement or investment savings. If possible, they try to raise money from rich relatives and friends, or convince an individual or institutional venture capitalists to invest. Results vary.

Penny, a former consultant, said, “it’s very easy to raise money right now if you have access to a rich network.”

Hattan has little experience with pitch decks, and no VC friends, so she hired a consultant to pitch financiers on Fiddler’s Greens behalf. That’s proven harder than it looks, she said.

“Everyone thinks they want to invest in cannabis, and then once you start having the conversations, they realize there’s a lot of risk and it’s not the get-rich-quick scheme that everybody thinks,” Hattan said.

De Facto Redlining in 2019

This combination of heavy regulation without access to bank loans amounts to de facto redlining in 2019.

“It definitely looks that way and, in some cases, it is,” said Chavez.

“It is absolutely a metaphor for what’s happening,” said Penny, who pointed to Florida’s regulations as “the definition of redlining.”

Under Florida’s original medical marijuana rules, medical cannabis license applicants had to have 30 years of commercial nursery experience and $5 million in the bank. “That is the epitome of redlining applied to a new industry,” she said.

“Calling it ‘redlining’ is very accurate,” said Hattan. “I’ve seen a handful of people that have been trying to bootstrap and that’s painful. People that were growing at their home, trimming at the kitchen table, cooking in their kitchen, and then selling into dispensaries—those people have been displaced.”

Mature Businesses Also Pinched for Funds

Cannabis startups aren’t the only businesses affected by this redlining. Mature cannabis businesses without financing are soft targets for takeover, Penny notes. Every day, small business profit margins shrink, and tax and regulatory costs rise. Meanwhile, their VC-funded peers can afford to bleed red ink for years.

“Capitalism is here,” said Hattan. “Some of our competitors are willing to discount their products so that they’re not even covering the cost of goods sold, just to put us out of business. It’s a really tough thing to deal with.”

Penny said, “Those larger competitors with deep pockets are able to come in and say, ‘This is a great brand. I see they’re strapped for cash. I’ll buy it for nothing.’ It’s unfortunate, but that’s what’s happening.”

Solutions to End Redlining in Cannabis

Every day federal prohibition persists, de facto redlining worsens. So, ending federal cannabis prohibition is the fastest way to capitalize small and minority operators. Lifting prohibition would end the risk of asset forfeiture, and thus allow banks to lend.

“When that safety net is there, the lending will open up,” said Chaves.

Beyond that, state politicians can reduce cannabis’ heavy licensing restrictions, regulations, and taxes—all of which benefit large, well-financed players at the expense of bootstrapped startups.

For example, Penny pointed out that Maryland allows just 15 licensed operators, all large, to serve the entire state. “Open up the number of licenses and have a mix of large, medium, and craft producers,” she advised.

The costs of a single rule change can break a small business, so the rules have to get simpler. “Compliance is expensive,” said Chaves.

“I’m not spending as much time working on setting investor meetings as I should be,” said Hattan. “I’m running the business.”

State and federal tax rates also need to be adjusted if small businesses—which operate at higher costs—are to have any profit margin. The federal tax code disallows most tax write-offs that small cannabis businesses need to survive, lowering their profit margin from 70-75% to “usually under 20%,” said Chaves.

Pending Action in Congress Could Help

On June 28, Small Business Committee Chairwoman Nydia M. Velazquez (D-NY) introduced HR 3540 to make small cannabis businesses eligible for federal Small Business Administration loans. Co-sponsor Rep. Jared Golden (D-ME) said, “continuing to turn some Maine small business owners away from crucial SBA programs and resources holds our economy back and keeps those businesses from creating jobs.”

Chaves notes that, “we’re never going to get rid of heavy regulations.”

A separate bill, HR 3544, would create an SBA grant program to give state and local bureaucrats money to help small businesses navigate all the red tape. The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Dwight Evans (D-PA) said, “We need to make sure that the booming legal cannabis industry does not become consolidated in the hands of a few big companies.”

The STATES Act would also legalize cannabis banking in states where adult use laws have passed, by exempting those states from the Controlled Substances Act—violations of which trigger asset forfeiture.

Don’t Give Up

All the experts encouraged individuals without wealth to get creative and be persistent to win their place in the legal cannabis industry.

Penny parleyed her career as a consultant into employment and equity with a growing cannabis company.

“Identify your value proposition and align yourself with folks who can access that kind of money,” she advised. “There are so many opportunities that don’t require a couple million dollars to get started—professional services, accounting, marketing, and business management folks are able to make their way that way.”

“Black women have become accustomed to leveraging our resilience and resourcefulness to make progress when everything is stacked against us,” she said.

Chaves said, “Once everything gets worked out, it’s going to be a very flourishing industry with even more opportunity than it is now for the smaller guys.”

“It’s still a very new industry,” Hattan said.

Fiddler’s Greens has launched High Tide Distribution, an education-based cannabis distribution company focused on giving heritage craft brands access to manufacturing and distribution. “I think there is a place for the legacy companies making quality products to survive this transition. We have medical patients who depend on Fiddler’s Greens tinctures and have had success when other products have failed. Our brand loyalty is very strong!”

And if we don’t end prohibition soon?

“The unregulated market will continue to thrive,” said Penny. “In places with exorbitant barriers to entry, you see the lack of participation in that market.”Late Capitalism Got You Down?