Is Weedmaps in hot water with federal prosecutors?

Federal prosecutors demanded Weedmaps business documents dating back to the company's 2008 founding.

Since news of a grand jury subpoena against the popular cannabis finder web site leaked earlier this month, the general legal consensus is ‘maybe.’ But exactly how hot the water is remains unclear.

Experienced attorneys say federal prosecutors could potentially criminally indict Weedmaps for alleged violations of drug, banking, tax and/or communications laws. Or they could use Weedmaps to go after bigger fish like corrupt state officials, or illegal pot shops undercutting the legal market. Or it could be all three.

Grand jury subpoena issued

In September 2019, Weedmaps received a subpoena to appear before a federal criminal grand jury later the following month in Sacramento. Grand juries and their subpoenas are confidential, but news of this one leaked on the web in late February. A close read of the subpoena hints at what the feds are after but leaves a lot of questions unanswered.

'These guys were sabotaging the entire system.'

This was a roto-rooter request. The US Attorney in the Eastern District wanted Weedmaps to come in, drop their drawers, and bend over for a full check-up. Sorry to get so graphic, but they want pretty much all business documents since Weedmaps opened in 2008.

It names 25 people from the company including co-founder Justin Hartfield, nine outside investment companies, and 30 other businesses or individuals. The feds want the corporate documents, everyone’s names, addresses, telephone numbers, the full identities of all managers, and the company’s human resources data. Also included: All calendars, notepads, contact lists, and diaries, all the company’s finance and tax info, and all information about outside business deals.

Weedmaps: ‘We cooperate with these requests’

A Weedmaps spokesperson responded last week to Leafly’s request for comment on the subpoena.

“Given our role as the largest technology company in the cannabis sector, from time to time, Weedmaps receives requests for information from government agencies,” the spokesperson said in a statement sent to Leafly. “We cooperate with these requests as we do with all lawful inquiries. Our corporate policy is not to comment to the media about any specific legal matters or inquiries with respect to the company or any of its customers.”

Company officials also told MarketWatch on March 3 that they are cooperating with federal investigators in a routine probe.

Flagrantly advertising unlicensed stores

That cooperation is a stark turnabout from the last two years, when Weedmaps publicly advertised unlicensed cannabis stores in California and rubbed state regulators’ noses in it. Some stores on Weedmaps advertised illegal, untested, and possibly tainted vape pens like Dank Vapes, that are associated with 70 ill and four dead in the state.

“These guys were sabotaging the entire system,” said Omar Figueroa, a longtime cannabis criminal defense attorney based in Santa Rosa, CA. Figueroa’s book Cannabis Codes of California: Legalization Editionis the standard resource for legal compliance. “It’s part of the reason why the regulated market is unworkable for honest operators who play by the rules.”

Born in the wild west medical days

Weedmaps.com was started in 2008 by Justin Hartfield and Keith Hoerling, two young Orange County guys with a background in flipping domain names and a knack for search engine optimization.

The site served a vital need, connecting patients with thousands of unregulated medical marijuana collectives in the state. The company enjoyed an open playing field for eight years, accepting listings from all comers in California’s Wild West medical marijuana days. Stores paid thousands of dollars per month for pins on the app’s map.

That changed in November 2016, when Californians voted to legalize and regulate adult-use marijuana. California went from several thousand collectives, many of them unregulated storefronts, to about 600 licensed stores and delivery services today.

Licensed and regulated sales began on Jan. 1, 2018. As of that date, only state-licensed stores could legally sell medical and/or recreational cannabis in California. In order to ease the transition, state lawmakers allowed some legacy medical marijuana collectives—holdovers from the medical Prop. 215 era—an extra year to get their licensing in order.

That transition ended on Jan. 1, 2019, when the collective defense was repealed. Collectives became illegal.

Failing to evolve

Weedmaps began aggravating California regulators in early 2018 by continuing to list unlicensed stores and couriers. Weedmaps executives received a cease and desist letter from California’s Bureau of Cannabis Control on February 16, 2018, but neither ceased nor desisted for more than two years.

Leafly, which competes with Weedmaps for cannabis store listings, announced on Feb. 27, 2018 that the site would be de-listing unlicensed stores on March 1, 2018. No unlicensed stores have been listed since that date.

Legal stores complained that Weedmaps undermined them by listing illegal sellers, who skirted taxes and regulatory costs.

After Jan. 1, 2019, legal cannabis industry operators and regulators began complaining loudly that Weedmaps continued to list and accept payments from unlicensed stores and couriers. Licensed operators argued that listing illegal stores and services undermined the legal market. Unlicensed sellers had none of the burdensome costs of state licensing, which allowed illegal sellers to undercut legal retailers on price.

Weedmaps responded by announcing on Sept. 9, 2019, that the company would wind down unlicensed businesses on its platform by the end of 2019. Meanwhile, the VAPI lung crisis exposed the public health hazard of listing sellers of illegal products.

Self-verifying companies

A Weedmaps spokesperson acknowledged the issue of illicit products, and said the company had taken proactive measures to combat the problem.

“Counterfeit products are a real problem in the cannabis industry, with bad actors trying to exploit sites such as Yelp, Leafly, Instagram or our own platform to reach consumers,” said the company official. “We identified this issue early, and in 2017 we launched the Brand Verified program, which allows brands to verify stores and products to help consumers identify genuine products.”

Mystery: Why feds and not the state?

The main beef here seems to exist between California state regulators and Weedmaps. So why are the feds getting involved?

Leafly contacted Henry Wykowski to provide some insight. As a former federal prosecutor, Wykowski knows how they operate. He also knows the cannabis business, having built up one of the most respected private practices in the industry.

Wykowski said it’s common for state regulators to pick up the phone and call federal prosecutors when they need help with a stubborn legal case.

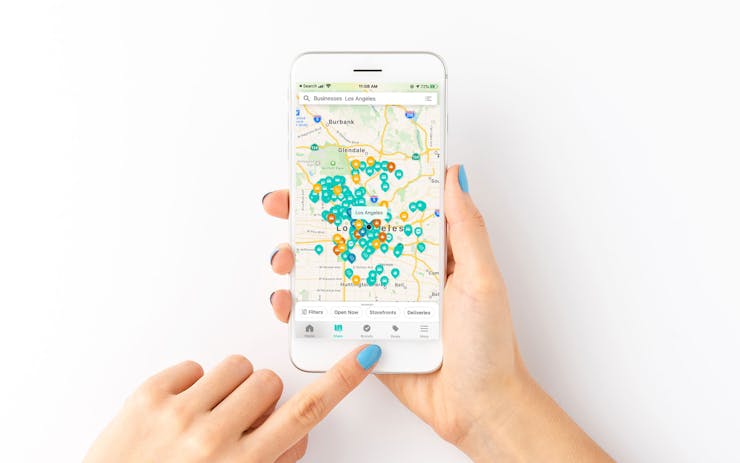

Looking for legal cannabis? Leafly’s app finds licensed stores near you

“That does occur,” he said. “There’s no question about it. When the state feels the federal government could do a better job, they do solicit their assistance.”

Criminal defense attorney Omar Figueroa said maybe Weedmaps executives should have pivoted while they still could. “They rode the pony until it died,” Figueroa told Leafly. “They had a beautiful business model and they could have kept killing it. Instead, they kept advertising unlicensed operators, thus undermining many struggling to survive in the regulated market. It’s a classic story of greed and overreach.”

Enforcement fits post-Cole Memo criteria

If you look at the larger context, Weedmaps’ 2019 activity places them squarely in the box for potential federal enforcement.

The Trump Administration and current US Attorney William Barr have little love for cannabis. They’ve instructed federal prosecutors to prioritize cases involving violators of both state and federal law, especially where it involves large-scale marijuana trafficking or sales to minors. The guidance mirrors the instructions issued in the Cole Memo, which was issued under President Obama but later retracted by former Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

Allison Margolin, a longtime Los Angeles criminal defense attorney, said that to her knowledge federal prosecutors have not indicted a single state-compliant cannabis business in the past four years. The feds have instead stayed busy shutting down flagrant interstate traffickers and unlicensed mega-grows.

Then again, maybe not

Margolin emphasized that Weedmaps is “not necessarily” in hot water with the feds.

Any non-licensed company that buys a Weedmaps ad self-incriminates.

Wykowski agreed. It’s unclear if Weedmaps is a target, a potential target, or merely a witness in this case, he said.

One potential strategy: The feds use of Weedmaps as a honeypot to roll up illegal businesses in California. Any non-licensed company that buys a Weedmaps ad self-incriminates.

“The fact that [Weedmaps is] cooperating doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence if you’re an illegal actor,” said attorney Omar Figueroa. “They’re radioactive at this point. Saying, ‘We’ve always been radioactive’ doesn’t help their case.”

Why are other legal companies named?

Weedmaps’ subpoena is widely expansive, attorneys say. It asks for sales, contract, banking, and contact information going back to 2008. The subpoena even asks for a copy of the company’s retail sales training manual.

However, the subpoena also specifically asks for documents related to 30 California businesses or people. Some of them very prominent and compliant in cannabis, like CannaCraft. Others are more obscure. It’s a wide net. Some businesses on the list—including CannaCraft—have appeared in other state or federal criminal cases, for one reason or another.

CannaCraft paid local officials $510,000 in 2018 to settle charges of manufacturing cannabis extracts without a license. The activity occurred in 2016, when those rules were in flux.

Officials at the company Terra Tech cooperated with federal investigators in a 2015 union bribery case against the state’s former top cannabis union official, Dan Rush.

Figueroa said it’s unclear if the feds issued Weedmaps and the other business simultaneous subpoenas. That’s a common tactic meant to corroborate a story or flush out suspicious activity. If two parties’ responses to the same question differ, Figueroa explained, “that often sets off a red flag.”

Something bigger than Weedmaps?

Still, Wykowski thinks US Attorneys aren’t looking for an easy, ticky-tacky wire fraud case against Weedmaps. “I don’t think that’s what this is about,” he said.

The subpoena specifically asks for documents on deals between Weedmaps and investors, or public officials, or banks.

That’s an important facet, because FBI officials stated in 2019 that the agency is focusing on pay-for-play corruption involving public officials and cannabis companies.

The most famous example of that is the recent case involving Lev Parnas, the Trump-connected Ukrainian fixer, and three other men in Nevada. In October, federal prosecutors indicted them all on charges involving election fraud in an alleged attempt to obtain cannabis licenses in and around Las Vegas. The previous month, federal prosecutors indicted the mayor of Fall City, Massachusetts, on extortion charges for allegedly offering city approval of marijuana licenses in exchange for hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes.

At the same time, federal authorities have been expanding their ongoing investigation into corruption within the City of Los Angeles. Former LA City Councilman Mitchell Englander was charged earlier this week with accepting gifts from a businessman in a pay-for-play scheme. The Los Angeles Times said this about the ongoing investigation:

“Agents have been seeking evidence of potential crimes including bribery, kickbacks, extortion and money laundering involving more than a dozen people, according to a search warrant filed more than a year ago.

Those people include Huizar and aides in his office; Councilman Curren Price, who represents part of South Los Angeles; Deron Williams, who works as a top aide to Councilman Herb Wesson; and former Department of Building and Safety chief Ray Chan, as well as other city officials and business figures.”

In other words, this case might target Weedmaps, or just leverage Weedmaps’ trove of documents as a way to ferret out public corruption or other wrongdoing.

What happens next?

It’s not clear what happens next. Prosecutors could indict Weedmaps officials tomorrow, sometime later this year, or never.

Weedmaps’ massive subpoena was so broad, it could take years for investigators to sift through their data. “Prosecutors gave Weedmaps some guidance on this, but [prosecutors] can’t force you to organize it in any particular manner,” said Wykowski. “They could just upload it all to a Drobox file and say, ‘Here you go.’

And US Attorneys are loathe to level charges that cannot stick, said Wykowski.

“Nothing may come of it,” Wykowski said. “They may do all this gathering of information and decide there just isn’t enough here to secure a conviction. They’re not going after cannabis entities aggressively anywhere in the country. They wouldn’t want to take on a case where there was any question that they would prevail in a trial.”