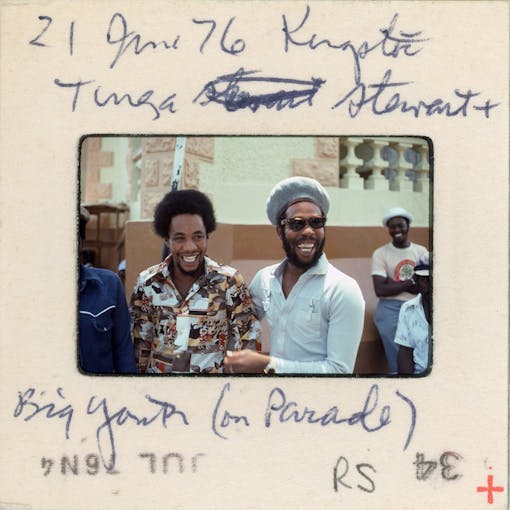

February 6th, 1945, is a day remembered by many who loved Bob Marley, the musician, songwriter, Rasta, and humanitarian. Photographer/writer/DJ Roger Steffens was a good friend, and has written several books on Bob’s life and music. In 2016, Roger’s unique personal photos appeared on the Instagram @TheFamilyAcid and the first The Family Acid book was released. This month, the newly published, The Family Acid: Jamaica book is out featuring 40 years of photos from June 1976 to March of 2016.

It was my pleasure to talk with Roger about Bob, Jamaica, and reggae music while we smoked some of his local Echo Park Shitface.

Roger Steffens

Leafly: How did you find reggae?

Roger: I discovered it in in ‘73 through an article in Rolling Stone by a gonzo journalist named Michael Thomas from Australia, who said that reggae music crawls into your bloodstream like some vampire amoeba from the psychic rapids of upper Niger consciousness. Oh? Okay! I’ve got to find this right now!

I was living in Berkeley, so I went down to Shakespeare and Co. on Shattuck, a used books and record store. I found a used copy of Catch a Fire for two and a quarter, the one that opened up like a Zippo lighter, and took that home. I’ve never heard anything like that before. Right from the first notes of the first song, “Catch a Fire“, and then “Concrete Jungle.” The next night at that little tiny revival movie theater on the north side, I saw The Harder They Come and bought the soundtrack on the way home. My life changed forever. That’s a turning point; it just completely shifted my interests and my life. That was 44 years ago, and it’s been on that trod ever since.

Leafly: How did you meet Bob Marley?

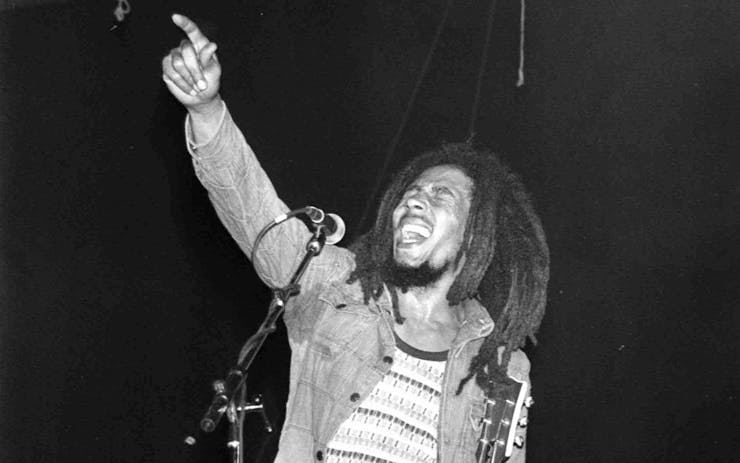

Roger: In 1978, I was hired by a couple of Hollywood screenwriters to novelize two of their screenplays. We rented a gorgeous A-frame on a mountaintop in Big Sur, looking right down towards the ocean. While we were there, Bob was playing two shows at the Santa Cruz Civic, so we got tickets for both of them, which was in July of ’78.

We were among the first people to get in the venue and as I walked in, I saw a soundboard right in the middle of a dance floor. It was like a high school gym, with three sets of bleachers. There was this tall, skinny guy with small nubby dreadlocks starting to sprout and I figured he must have something to do with the band, so I said, “Pardon me, sir, are you guys going to do ‘Waiting in Vain‘ tonight?”

“He’s been dead as long as he lived, this is 36 years following his passing. Alive for 36 and gone for 36.”

And he looked at me kind of funny and he said, “Why?” I said, “That’s my favorite Bob Marley song, especially that incredible leading guitar lick, that Junior Marvin plays.” And he said, “You want to meet Bob?” “Yeah, really? Yeah! Can I bring my wife?” He said, “Yeah, sure.”

We go down this long, long corridor to get backstage and he asked, “What’s your name?” I said, “I’m Roger and this is my wife, Mary.” He said, “Hi, I’m Junior Marvin.” I said the right thing to the right guy, at the right time.

We walk in the back room, and it’s like a convention of zombies, nobody’s talking to anyone else. There’s four huge cafeteria tables all pushed together to make this giant table and everybody is at least this far from anybody else and they’ve all got mounds of marijuana in front of them with their own individual packs of rolling papers. Nobody’s saying anything to anybody. I had a poster that somebody was giving out in line as we were waiting to get in, advertising a show three days later at the Greek Theater. Junior said, “Why don’t you ask Bob to sign it?” and I say, “Oh, oh, yeah.” I was so awestruck. He took me over and introduced me to Bob and Bob was so stoned and so into the Ites. I asked him if he could do “Waiting in Vain” tonight and he looked up and said, “Maybe.”

He never did it live, because his wife wouldn’t sing backup on the song since it was about another woman. Supposedly about Cindy Breakspeare, the greatest love of his life. Damian’s mother, Ms. World 1976. He never did it and I never got to hear it live. But then, he took me around and introduced me to the whole band and they all signed [my poster].

That night was the night I met Bob. The following year, Hank Holmes and I finally, after a year of trying, got on the radio here. A reggae show, and at that point there were no other reggae shows in L.A. at all. KCRW finally agreed to put us on. I was the first person Tom Schnabel brought to the station after he became music director.

My partner Hank and I started the show on October 7, 1979. The following month, Bob was coming to L.A. Island Records, his label, called us up and asked us, “Would you mind going on the road for two weeks with Bob Marley?” Twist my bleeding arm! So we did. The happiest guy on the road was the bus driver, because he got to sweep up all the roaches each night. We became friends and it was a lovely time.

Leafly: What was he like?

Roger: Very quiet and very observant. The whole room, whether there were five people or 50 people, they all swam in Bob’s current. He set the tone.

“He was a prophet. He knew a lot of things that astonished people.”

He was a watcher and deadly serious. He could laugh, but he was here on a mission and he knew he only had a short time. [When he was] twenty-four in 1969, his mother had left about seven years earlier to marry a man in Delaware. He spent that Woodstock summer of ‘69 with her there. He told a couple of young men–I’ve interviewed both of them, and his mother has confirmed this story–Bob told these two young guys in ‘69 at the age of 24 that he was going to die at the age of 36, no question about it. “I know I’m going to die at 36.” Weird thing for a kid to be thinking about, or saying. He did die at 36.

He was a prophet. He knew a lot of things that astonished people. He often would meet a total stranger and tell them all about their life and stagger them, policemen, women in the village where he was born. He was doing it from the time he was like three and a half to four years of age. He was reading pa

lms and telling fortunes, and [he was] stone cold accurate. A lot of those people came to his mother and said, “Hey, keep an eye on this kid, there’s something going on here.”

Leafly: What was it like to come into the Rasta circle?

Roger: I’m an observer of the Rasta culture; I don’t think it would be fair for me to call myself a Rasta. I’m sympathetic to a lot of it, though.

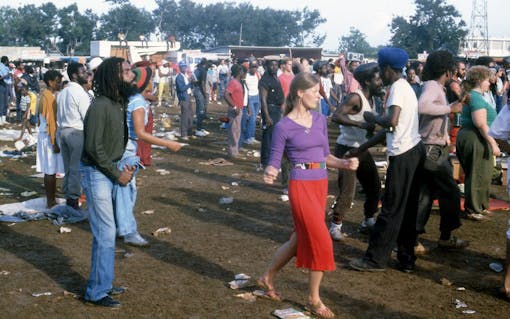

The first real touch I had of it was in 1976, when Mary and I went to Jamaica to find some rare records. By definition, reggae is rare. That was my first time in Jamaica and the week we arrived, Michael Manley declared a state of emergency, mobilized the army, put tanks on all the roads and I thought I was back in Saigon during the Tet Offensive. I just wanted to go buy records and we went to Kingston against everyone’s advice.

The streets were almost deserted. We took a minibus from the north coast, and we got dropped off at Bob Marley’s record shack on a back street in Kingston, and one of the biggest reggae stars at the time picked my pocket in Bob Marley’s record shop! It was so unnerving. A half hour later somebody we met took us to Jimmy Cliff’s house and we spent the afternoon with Jimmy and a whole bunch of the early reggae stars. That’s a microcosm of Jamaica, right there in that first day in Kingston.

Leafly: What is so visually striking for you in Jamaica, as a photographer?

Roger: I think the topography, first of all, and going to Negril, which at that point was empty. It was only that Polynesian hut that the two Jewish dentists from Long Island opened for a dental clinic every winter, and gave free dental care to the people for four months. That was the only visible structure for seven miles. Now it’s built up on both sides of the road, all-inclusives telling people not to go out on the street and mingle with the locals because they’ll kill you and things like that.

Lush, green Jamaica

Leafly: You went to Jamaica at a turning point in Bob’s music; Rastaman Vibration had just come out.

Roger:Rastaman Vibration, the only top 10 album Bob ever had. I went to a Bob Marley record store and they had no Bob Marley records for sale.

He didn’t become a star in Jamaica until the British really embraced him in ‘75 and he did that live album at the Lyceum. He was a star abroad so they allowed him to be a star in Jamaica. This is after a dozen years of recording and making a whole lot of local hits. But he was just another group…

Leafly: What motivated the social message in his music?

Roger: A lot of things led to that for a long time. One was his living in Delaware that whole summer of 1966, and that was in the height of the Civil Rights movement and demonstrations and black power literature. He was exposed to all of that living in a black community in Wilmington. Then Haile Selassie’s visit gave him a firmer grounding religiously.

The country had achieved independence in 1962 and the right wing Jamaican Labor Party had run the country for the next 10 years, and people were pretty sick and tired of them. In ‘71 when Michael Manley ran for Prime Minister, he ran on a platform of [providing] help to the sufferers, and Bob campaigned with him even though Rasta eschews politics. But Bunny told me the only reason they played on this caravan of stars that went all over the island — they performed, and then Manley made speeches after — was that The Wailers were paid more money than they ever made in their lives. $150 dollars a night to sing at Michael Manley rallies, but that exposed him to politics and it exposed him to the folly of believing in politicians because they really thought that if Manley was elected he was going to legalize herb like that overnight.

Of course, he didn’t do anything of the kind. They felt really betrayed by him, and that’s where that line, “Never make a politician grant you a favor, he will only try to control you forever” comes from. That’s a personal response to what happened.

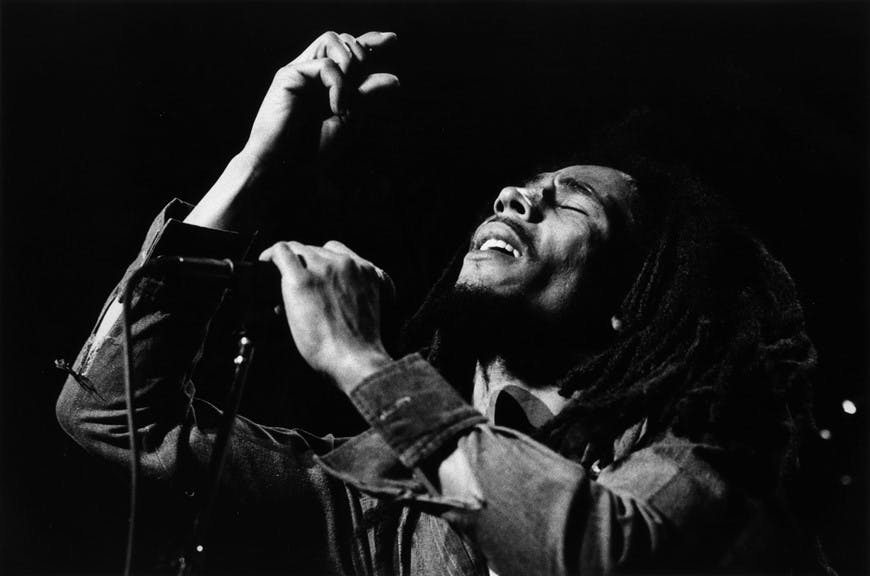

Leafly: How did marijuana tie into Bob’s message in his music?

Roger: When people say to me, wasn’t he smoking dope all the time, wasn’t he always stoned? My answer to that is all the great anthems he wrote, “Get Up, Stand Up,” “Exodus,” and “Redemption Song,” they were all inspired by direct use of herb. At the millennium, the NY Times said that Bob Marley was the most influential musician in the second half of the 20th century and the first half they said [was] Louis Armstrong – both daily herb smokers. I love that.

The first song I can remember him singing about herb was not until 1970, when he made “Kaya.” Kaya is herb; [it’s] also the straw they put in mattresses, so it had a nice double meaning. He really believed that it was the way you can communicate with Jah, the overlying spirit, and all of those great songs were inspired by his conscious use of it.

He told me that marijuana was not just for jollification, it was for “headucation” as well. I’ll never forget that, so it was a means to an end, a means of “I and I” relationships. “I and I” means “you and me,” it means “God and I,” it means “God in I.” It is the oneness of all things; it directly led to “One Love,” which is the anthem of the millennium. People all over the world know that song.

Somebody asked Peter Tosh once if music can change the world and he came up with the very best answer. He said, “No, but music can change people and people change the world.”

Leafly: How do you feel legalization will impact pot subculture as it goes mainstream?

Roger: My greatest fear, and it’s been evidenced in Jamaica where it’s been legalized in the past year as well, is that people who suffered for it all these years to provide us with herb will be cut out of it while the major corporations and the big tobacco companies take over the field. That is my greatest fear, that they get really greedy and want to tax it so high that the underground just flourishes again because you’ll get a much better price and you know who your supplier is.

That’s my main response to legalization, but thank God nobody’s going to be thrown in jail anymore. But all those poor people who went to jail and now they say, well you can’t have a dispensary because you were in jail, that stinks. That really sucks. And God knows what the Justice Dept. is going to do now. They can crack down on pot as long as it’s Schedule I according to the Feds. It’s all these fascist creeps, they’re afraid somebody somewhere is having fun.

And I dropped acid almost two years before I ever smoked my first joint.

Leafly: Really?

Roger: Dropped acid, pure Sandoz, in Milwaukee. I was a member of the Milwaukee Repertory Theater and I knew these guys who had like a sack that big, like almost a basketball, and it was like powder sugar. It was pure Sandoz they had ordered from Switzerland when it was still legal. They were packing caps by hand so they were getting stoned through their fingertips, and they were awake for like seven or eight days and nights and they were just having so much fun.

I was a good Catholic kid; I didn’t deal with any kind of drugs. I didn’t smoke cigarettes or anything and you know, they were having so much fun, I finally decided, fuck, I got to try this and it was really good. So, if you’d had an H-bomb, what do you need a firecracker for?

There wasn’t a lot of good herb around in those days, so I got to Vietnam and I needed something to cut the tension. There were no front lines, it was guerrilla warfare and there were people being blown up on the street in front of my house. I needed something. I didn’t want to drink because if you’re drunk, you’re drunk; you’re not going to sober up. But if you’re stoned on herb, you can straighten up pretty fast if you get that adrenaline rushing. We smoked repacked cigarettes full of commie weed called Park Lanes.

This was commie weed and it was really good. It was 25 cents a pack of 20 or a carton of 200 for 2 dollars, a penny a joint, but it was all commie weed and it was really great. There were like three different strains that they would put in, one of them got you off with like two hits, then the next was Hamburger Helper, it just kind of elongated the high a good long time. The third was roasty, toasty, psychedelic mind melt, hand trail. Yeah, so I stayed stoned for the entire war.